This essay attempts to overcome the inadequate understanding of cycling as a mere sport, leisure and even transportation activity. It opens up a different perspective from critical cultural studies to look at cycling as individual and collective tactics that shape and are shaped by everyday practices and have the potential to challenge existing socio-spatial dominant regimes.

I have used Michel de Certeau’s concepts of tactics and strategies in The Practice of Everyday Life, which offers a new approach to understanding everyday life, to look at our everyday cycling practices and routines in Tehran as a contested context. From this perspective, cyclists are active agents who have the power to transform the city and society.

For de Certeau, strategies are seen as “the calculation (or manipulation) of power relationships that becomes possible as soon as a subject with will and power (a business, an army, a city, a scientific institution) can be isolated” that structure our everyday lives and . He defines tactics as “a calculated action determined by the absence of a proper locus” (Certeau, 1998: 35-36) and which intervenes in the power mechanisms within everyday life. Strategies are imposed by the system and tactics are used by those who have less power.

I focus on the idea that the bicycle is a critical tool and everyday cycling is an emancipatory practice and a form of resistance in socio-spatial hegemonic contexts that can challenge power relationships. It has a transformative power to Take Back Our Streets and Transform Our Lives by making everyday life critical.

Occupy the Space: Ride in between

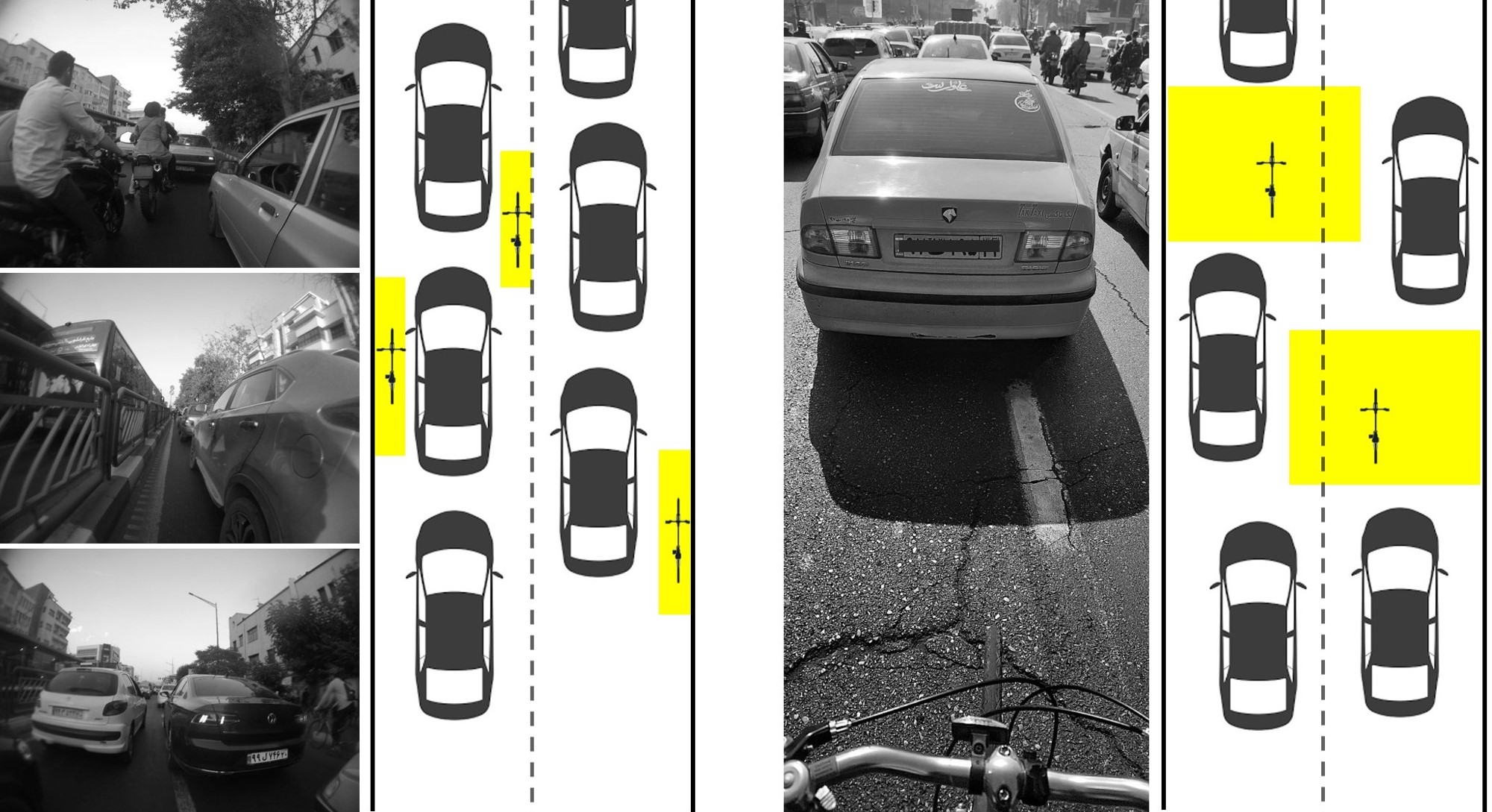

Tehran is a car-dominated environment with a strong car culture in which the entire space is taken up by motorized vehicles that impose space limits on cyclists and pedestrians. In this context, I am an “other/outsider” and must ride on the edge of the street, using the space between or next to the cars, and my body obeys the hegemonic spatial order. However, if I decide to place myself between the car in front and the car behind and occupy a space the size of a car, this is a kind of break with the rules of the road and is seen as a tactic to challenge the existing motorized hegemony.

In this space-power situation, the car behind me usually honks its horn to pull me to the edge of the space. But I resist the imposed order by pedaling quietly in the middle of the car-centered streets. This is a critical practice and a form of resistance in the everyday life of a cyclist in such a car environment, to restructure everyday life by occupying the space. Whose belongs to the space?

Slow pedaling: Manipulate the time and challenge hegemonic rhythms

Another mobile tactic is to dampen the motorized rhythm of the street by pedaling slowly. A cyclist’s slow riding is a critical practice in an environment where the street is defined as a mass transit space and must connect A and B in the shortest possible time. It is an isolated and mechanical connection to the urban space that reinforces the motorized rhythm of the street.

The driver is concerned only with steering himself to his destination, and in looking about sees only what he needs to see for that purpose; he thus perceives only his route, which has been materialized, mechanized and technicized, and he sees it from one angle only – that of its functionality: speed, readability, facility .

(Lefebvre, 1974: 313)

But cycling creates an alternative rhythm of everyday life, a rhythm that goes against the mechanical and machinic cycle of time that prevails in car-oriented environments like Tehran. My slow pedaling in the streets of Tehran is a tactic to challenge the existing rhythm and dominant automotive discourse. The cyclist is not a passive mobile, but an active agent that can challenge hegemonic structures.

Conversation on the bike: Challenge the street as a transit corridor

Urban spaces are technically part of the public domain, but ideologically they are constructed to facilitate certain forms of mobility and restrict others; a process that creates a certain hegemonic transportation system in the city. Is the urban space a place of high-speed traffic that connects the starting point to the destination, or is it a social space for encounters between people? In Tehran, the street is often understood as a transit corridor for cars, a functional space that is understood as a “road” and where any kind of pause is unacceptable.

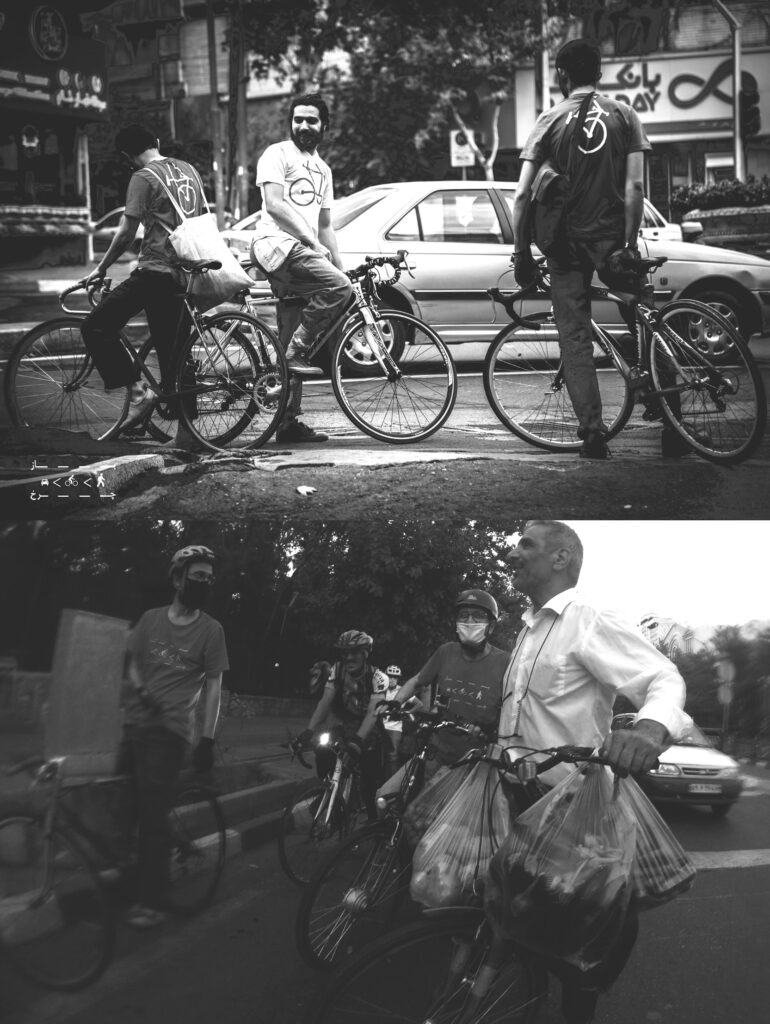

For cyclists, on the other hand, the street is not just a functional corridor connecting A to B, but a social space where a human relationship and an intimate, meaningful experience of the city are possible. Bicycles trigger the first spark of our acquaintance and easily bring us together.

When I cycle, I have close social contact with my cyclist friends on our bikes (directly) and with other cyclists and pedestrians on the street (indirectly). Cycling implies an intimate and engaged connection with the human and non-human environment and is an alternative way of experiencing the city, distinct from the mechanical movement of automobility.

Cyclists establish a direct, bodily, and social relationship on the bike, whereas there is no such relationship behind the car window. We greet each other when we see each other on our bicycles in Tehran, while as car drivers we only warn each other by honking our horns. This is a tactical practice that reverses the street discourse in our car-dominated context. Should we move fast or pedal slowly and engage in social interaction on the street?

Women’s cycling; Make the invisible, visible!

Cycling in Tehran not only fights against the car-centered streets but also misunderstandings and dominated car logic. If you are a woman, it is even more than that; the bicycle is an emancipatory tool to transform lived space and cycling is a practice to represent power and challenge hegemonic socio-political structures from below. This battle is fought with gendered mindsets and many false assumptions. The last decades of policy in Iran have restricted women’s activities to indoor spaces or urban parks to make them invisible in the city and society.

However, women’s cycling in public spaces makes them visible in urban theatre, tactically challenging gendered spatial strategies as they move through the city and play their role as visible actors. Women see cycling as a political practice to challenge everyday regimes. While there is no official law preventing women from cycling here, their cycling practice is questioning unwritten rules and political norms.

In my society where women’s rights are a pressing issue, cycling can be a way to challenge the dominant patriarchal discourse. The freedom of movement and independence that cycling brings can have multiple effects on the micro-dimensions of women’s daily lives, and bring about far-reaching changes in the gendered structures of society and environment. Cycling is a tactical practice to challenge gender-based hegemonic strategies; Making the invisible, visible!

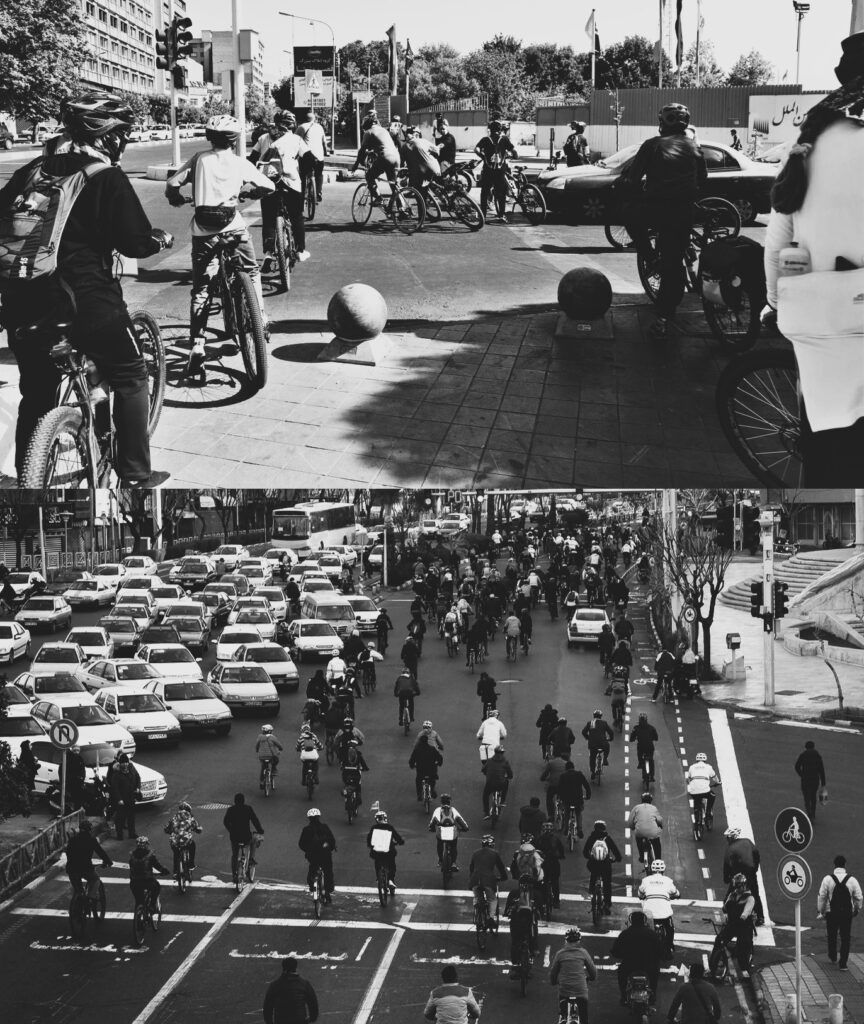

Accumulation of mobile bodies: Collective riding and question of the dominant order

Collective riding on the hegemonic streets challenges how urban space should be used; it distributes the dominant order and strengthens the social bonds between marginalized people. Riding together becomes an act of collective solidarity, which Cox (2018) refers to as ‘counter-hegemonic practice’. Our group pedaling in the streets of Tehran is a collective tactic that disrupts the imposed order of space.

“Before producing effects in the material realm (tools and objects), before producing itself by drawing nourishment from that realm, and before reproducing itself by generating other bodies, each living body is space and has its space: it produces itself in space and it also produces that space”.

(Lefebvre, 1991: 170)

The accumulation of disobedient bodies of cyclists creates a critical mass that represents different spatial alternatives. We use our entire bodies and muscles to produce our own spaces and represent alternatives to being and living in spaces. In carnival cycling, we ride slowly, talk to each other, look around and challenge the hegemonic order of the street. It is a bodily protest on the street, where our bodies critique the belief that spaces should be functional and bodies docile. This is our counter-hegemonic tactical practice.

The bicycle is a seemingly simple tool, but a complex and intertwined phenomenon with cultural, social, political and environmental aspects. It should be seen as an ethical and critical tool against the spatial strategies of urban regimes especially in socio-politically contested contexts.

References

- Cox, P. (2018). Cycling: A Sociology of Velo-Mobility. Milton: Routledge.

- De Certeau, M. (1984). The Practice of Everyday Life (S. Rendall, Trans.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991 [1974]). The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith, Oxford: Blackwell.