The following text is the accepted version of the book review by Meredith Glaser and Sean Mottles published in the academic journal Transport Reviews:

What is it about?

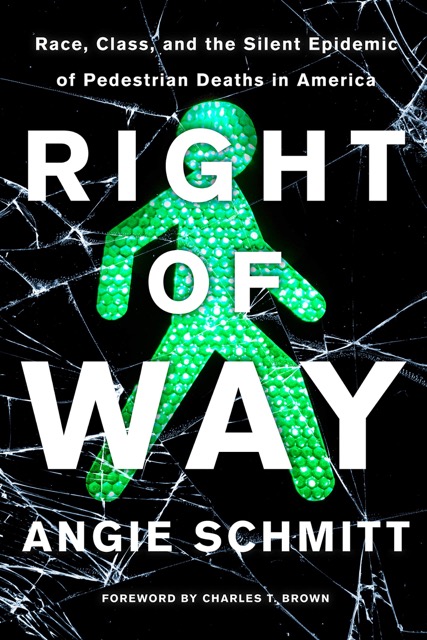

An archaic principle continues to dominate the design and use of streets in the US: by prioritizing the amount and flow of car traffic streets can handle, cities across the country accept the dire consequences to human life, especially those most vulnerable in society. This is the main premise in Angie Schmitt’s book, “Right of Way: Race, Class, and Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America,” which boldly weaves many heart-wrenching stories related to policy, infrastructure, and cultural failures that result in the cold fact that every ninety minutes someone is killed as they walk or cycle American city streets. In ten chapters, Schmitt adroitly confronts such traffic violence as the interface between racism, victim-blaming, SUV arms races, and federal design policies that all contribute to a growing public health crisis brushed aside for decades.

Chapters 1 – 4 interweaves demographics of traffic violence victims, the hostile urban environments they navigate, and the socio-political systems that work against them. Schmitt asserts that car-dominated urban environments treat people walking and cycling “as an annoyance or irritation, a potential obstacle” (p. 29). Culturally, she argues, culpability has shifted from the operator of a vehicle to the receiver of the operator’s negligence. That mindset has been systematically advanced for decades; now that it is culturally accepted, deaths and injuries are regarded as “tragic but inevitable” (p. 30). Nested in these cultural ailments, Schmitt denounces many planning practices that continue to oppress vulnerable, under-presented, often communities of color. A lack of basic road infrastructure in low-income neighborhoods leads to disproportionate negative health outcomes. Housing unaffordability pushes low-income populations either into suburbs, that were never designed to accommodate their walking or transit needs, or into homelessness. Either choice continues to limit mobility options while increasing risk of injury or death.

In chapters 5, 7, and 8, Schmitt provocatively tackles vehicle design, technology, and rising popularity of increasingly larger personal cars, specifically sports utility vehicles (SUV). Schmitt critically reprehends the automotive industry for rising traffic violence. Vehicles have been increasing in size and horsepower steadily from 1985 to 2015 (p. 204); however, without imposing safety standards on automakers to protect people outside the vehicles (p. 209), the likelihood of serious injury or death increases. While partial computer assistance, like automatic emergency braking, improves safety for those outside cars, Schmitt addresses the various implementation failures of self-driving cars, both in the lack of safety standards in testing environments and lack of accountability (p. 302). In short, technological advances, she warns, will do little to avert public harm.

In chapters 6 and 7, Schmitt chides federal policy, particularly the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), as outdated and heavily gender- and racially-biased, and offering little to no guidelines for accommodating pedestrians and cyclists. While Schmitt derides antiquated standards – formulated during the Eisenhower era (p. 235) and still in use today – novel insights into underlying reasons or how the standards might evolve would greatly support her efforts to convince the reader, whether practitioner or academic. Schmitt does commend organizations like the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) for their forward-thinking design guidelines; however, the reader may question to what extent these guidelines have been transformative. Some practitioners, say traffic engineers, may be left wanting a more practical discussion exploring potential resolutions for the tensions between outdated federal policy and the characteristics of city streets needed in urban environments today. With the impending revision of the MUTCD, such critical guidance would be welcome.

In the final two chapters Schmitt cites various places around the world, showing that loss of life is a deliberate choice and that traffic violence is not unique to the US. Schmitt mobilizes success stories; Oslo and Mexico City are front-runners (p. 341-346). While inspiring, many readers, i.e., in a US context, might be left pondering the transferable lessons. For urban planners and advocates, questions may include: How were community and environmental changes politically navigated? Which stakeholders or coalitions proved most beneficial?

What approach does it take?

In her concluding remarks, Schmitt rather successfully harmonizes a journalistic objectivity with soulful advocacy – certainly a fine line to balance. On the municipal policy level, she praises the practice of decreasing speed limits and building sidewalks in low-income areas; compliments are given to local efforts to galvanize momentum, such as Vision Zero and resources produced by NACTO. Holding accountable the auto-making industry is imperative for Schmitt. For urban and transport planning practice, she addresses the need to prioritize equitable transportation systems and to incorporate holistic designs into federal guidelines. Those who share her sentiments may feel the advice sounds familiar and is somewhat restrained. Here we circle back to the book’s main premise: the archaic principle prioritizing the amount and flow of car traffic. While building more sidewalks, painting more crosswalks, and installing more flashing lights might change car traffic flow, these measures do very little to curb the number of cars barreling through city streets. For a book that audaciously defends systemic change, some readers may be left pondering: does the current system need fixing or dismantling?

Further details

- Right of Way: Race, Class, and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America, by Angie Schmitt, Washington, Island Press, 2020, 248 pages, $25 (paperback), ISBN-13: 978-1642830835