What is it about?

Seeing Like a State builds a compelling case on how state-initiated social engineering, although based on honest intentions to improve the human condition, failed to recreate life, cities and production after its own image. Even worse, the high-modernism on which it is based, wreaks havoc on the very habitats and subjects which they intended to help. In discussing a diverse set of examples, from scientific forestry, to urban planning, to large scale villagization in Tanzania, Scott reveals the underlying mechanisms of how this unfolds and provides as such a rich understanding of what causes such perverse effects. His warning are especially sobering if you see that 20 years after publication, the high-modernist assumptions still prevail in our modern society, maybe even more than ever. One domain in which this can be seen in its full nakedness, is traffic engineering and the way in which we design our public streets.

According to Scott the four elements that provide fertile ground for state-initiated social engineering: [1] administrative ordering of nature and society; [2] a high-modernist ideology – a muscle-bound version of the self confidence about scientific and technical progress; [3] an authoritarian state willing and able to use its coercive power and; [4] a prostrate civil society that lacks the capacity to resist.

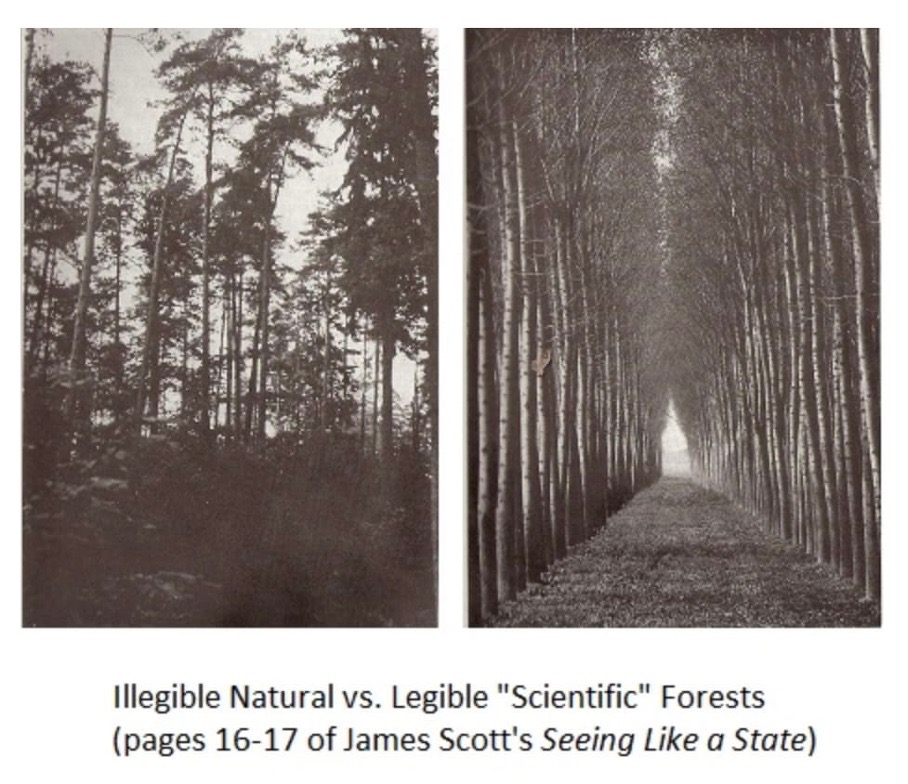

When these four elements are aligned, nothing stands in the way of ambitious redesigns of our society in line with prevailing ideas of what is ‘good’. But more often than not “at best, the new order was fragile and vulnerable […]. At worst, it wreaked untold damage in shattered lives, a damaged ecosystem, and fractured or impoverished societies.” (p. 350). So, why did this happen? Key in this lies in the strong belief in the superiority of positivist scientific knowledge that simplified complex social and spatial phenomenon into statistical information. The effort to make society ‘legible’ from above. The resulting insights could be used by “super-agencies” to crowd out all other forms of knowledge.

“Statistical facts were elaborated into social laws. It was but a small step from a simplified description of society to a design and manipulation of society, with its improvement in mind. […] I was possible to conceive of an artificial, engineered society designed, not by custom and historical accident, but according to conscious, rational, scientific criteria.”

p. 92

First, this is explored this for scientific-forestry, in which forests came to be seen as ‘natural capital’ that could be managed and improved in terms of wood production. Bracketing the forest into such a simplification creates a risk of becoming blind for things that lie just outside of it. That ignored external complexity not only meant that our forest became unhabitable for most flora and fauna, but also haunted the wood production itself.

The most powerful chapter for us is the discussion of the Corbuserian view of the ideal city, materialized in Brasilia. One of the key principles was “the death of the street” […] the complete separation of pedestrian traffic from vehicle traffic and, beyond that, the segregation of slow- from fast-moving vehicles. He abhorred the mingling of pedestrians and vehicles, which made walking unpleasant and impeded the circulation of traffic.” (p. 109) Sounds familiar?

By and large, Scott argues that it comes down to an overconfidence of the high-modernist priests: “The progenitors of such plans regarded themselves as far smarter and farseeing than they really were and, and the same time, regarded their subjects as far more stupid and incompetent than they really were.” (p. 343)

And, although schemes such as Brasilia and large parts of the principles of Le Corbusier have clearly failed, this way of thinking still underlies super-agencies such as our Ministries of Infrastructure and the traffic engineering manuals. Even worse, the streets that have designed in this image has likely had a huge impact on the humans and societies that use it as their public space. It probably “damaged earlier structures of mutuality and practice” (p. 349). And, as a large-scale version of a sensory-deprivation tank, it stupidifies the human subject.

The solution? Use small steps in interventions, favor reversibility, plan on surprises and human inventiveness. And always ask ourselves for any project or intervention: “to what degree does it promise to enhance the skills, knowledge, and responsibility of those who are a part of it?” (p. 355)

What approach does it take?

The book offers historical analysis based on secondary sources. As a result if offers insights in a wide variety of different cases that enrich the developed narrative about state-initiated social engineering.

Who might be interested in this book?

This book should be compulsory reading for everybody that works within or against institutions that can use their coercive power to put a stamp on social or spatial phenomena. Traffic engineers can use to reflect on the great responsibility they have and the humility they should bring into that. Activists and citizens can use it to understand how norms and guidelines are used to disguise political choices with a scientific cloak.

Further details

- Academic disciplines: Urban planning, sociology, history, political science.

- Geographical scope: Examples from across the globe (Brazil, Germany, Soviet Union, Tanzania)

- Relation to cycling: Gives a broader understanding of the forces that shape the political debate and the physical design of our streets. Although if refers to traffic engineering only on a few points, the critique of top-down social planning, is clearly applicable on transport. Key question that it raises: can be use the bicycle, and its related complexity, to find an escape for this? Are will it be appropriated and adapted into the dominant frame that has been solidified in the last decades.

- Reference (APA): Scott, J. C. (2020). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Veritas Paperbacks, Dublin.