What is it about?

Understanding Urban Cycling raises important questions around the much proclaimed Bicycling Renaissance, the slow return of cycling as a mainstream mobility mode in our cities. Central in his critical reflections are Spinney’s questions around who it is that is returning, what kind of cycling this entails, and why this matters. As such, it directly relates to the work of Ciamotto and Scott that raise our awareness about the importance of discourses (and understanding how Seeing Like a State influences our view on cycling). Far from being a neutral or strictly positive trend, Understanding Urban Cycling makes us aware that urban cycling is multi-faceted in nature and the policies that are embracing it strengthen only a part of that.

The first chapters really blew me away. They offer the foundations for a much-needed and sharp critical-constructive approach to study urban cycling patterns. Spinney points to some highly problematic observations about current trends, especially about the missed potential of cycling to challenge the underlying world views that have dominated out cities and mobility systems:

“What we see emerging is a ‘weaponised’ version of cycling that is more concerned to produce better human capital and faster circulation times than enable human flourishing […] to enable the work journeys of a minority rather than enhance the wellbeing of a diversity of citizens.[…] Current manifestations of urban cycling do little to question the dominant growth paradigm of production and consumption, rather they reinforce it.”

p. 2

There is an urgent need to move away from a growth oriented mindset, but instead of using the intrinsic qualities of cycling to support that, it is now often frames a better form of growth (often disguised in branding cities as liveable, sustainable and healthy). Cycling is inherently pluralistic and embraces multiple qualities; such as its playful and sensory qualities; its emotional and physical nature and its role in human flourishing. Yet in current policies and intervention it is by and large strengthening a narrow vision of cycling as a means to replace the car for a more efficient city and population, strengthening the individualisation and totalizing assumptions of neoliberal capitalism (p.20). As such it also attracts mainly a white middle class who ride from choice and marginalized communities who ride out of necessity.

Those who follow earlier work of Spinney will not be surprised that he is not passively observing this reality.

“I’m keen to provide an account that allows for feeling and sentient human bodies, rather than the passive, homogenous, disembodied user found in early political-economy and transport geography“

p. 29

As embraced in many counter-movements in the 60s, 70s and today, the very nature of cycling offers a strong symbol for ‘anti-economic’ thinking, in opposition to contemporary capital accumulation. But to use that potential, we need to be more aware of the discursive narrations that are currently used and its possible alternatives: “Given a different set of priorities, it may well be that other qualities such as sense of freedom or playfulness might be foregrounded” (p. 42).

In the empirical chapters, Spinney offers a rich kaleidoscope of insights in how these dynamics play out:

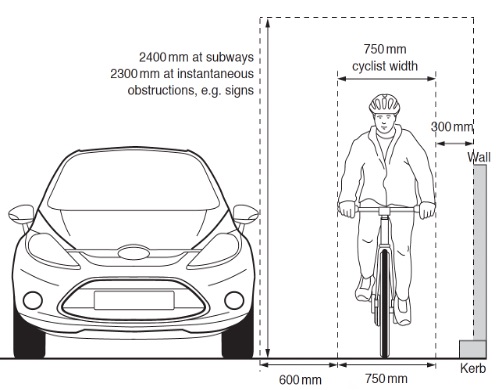

- In how design guidelines for cycling infrastructure centre around an adult, able-bodied, male commuting cyclist at the expense of other subjectivities. And data gathering attempts to reduce the act of cycling in line with other vehicle flows. As such, these choices severely solidify the future of cycling.

- In how cycling policies and practices in London directly relates to strengthening the neoliberal state, linking cycling as a solution (a mobility fix) to achieve higher productivity and lower obesity and sedentarism (or surplus value)

- In how cycling sub-cultures, such as BMX cycling or Trials, are co-opted/commodified as regeneration interventions. The spontaneity and dynamism of such cycling than adds value to retail- or other spatial developments

- In how cycling in Taiwan/Taipei draws upon a standardised repertoire of global imaginaries, while building on their local cycle-industrial image. Here, economic thinking is embedded within culture to create value

- In how dockless bike-sharing is leading to a controlled form of consumerism in which the cyclist produces valuable data to be extracted: “harnessing the labour of the cyclist to produce raw materials that can be manufactured into predictive products” (p. 202)

What approach does it take?

Building on earlier academic work with Dr. Wen-I Lin, the book offers in-depth interviews, diaries and document analysis.

Who might be interested in this book?

If there is one book on urban cycling you will read this year, make it this one. Especially if you are fighting to put cycling back on the menu, this work can help you to position yourself in terms of what the ideal cycling future could and should look like: “to rescue the cycling agenda from technocrats and economists and a potentially delusional decoupling fantasy” (p. 13). But it also offers a solid starting point for academics that engage, or start to engage, with cycling research. In a way, the book symbolizes the ongoing efforts to carve out specific cycling research thinking that embraces the full potential of the bike, such as the Cycling Research Board.

Further details

- Academic disciplines: Linguistics, sociology, urban planning, mobilities.

- Geographical scope: Empirical material from the United Kingdom, Thailand and Taiwan.

- Relation to cycling: Cycling is central in this book: in trying to understand how cycling is now leveraged to advance political agenda’s, and how this can be changed.

- Reference (APA): Spinney, J. (2021). Understanding Urban Cycling: Exploring the relationship between mobility, sustainability and capital. Routledge, New York.