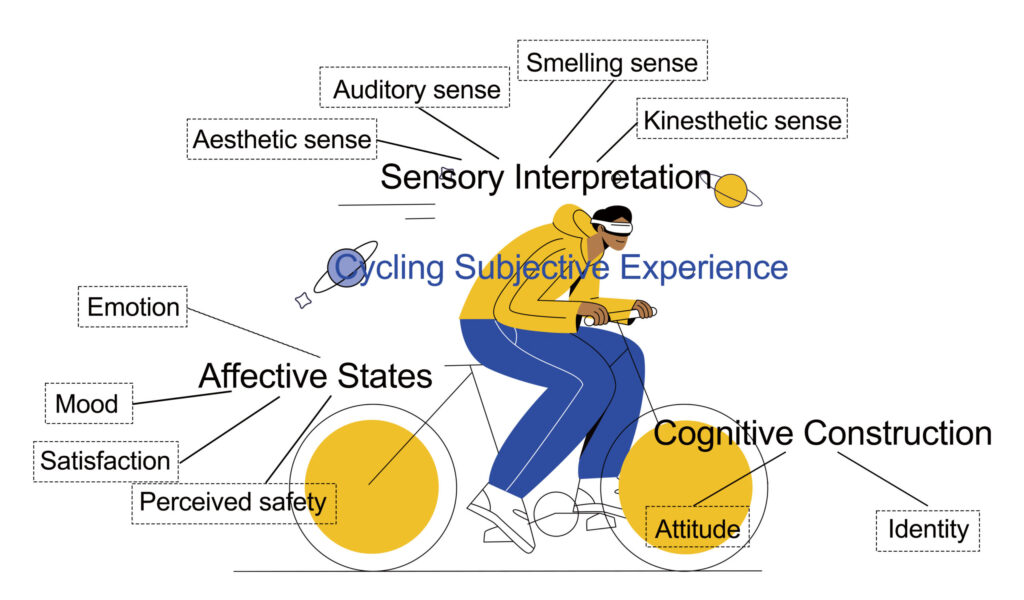

For many people, cycling is an important part of childhood. Not much is known about how children perceive various features of cycling across contexts, but existing studies have pointed to the importance of for example playfulness, sensory pleasure, mobile sociality, ‘coolness’, freedom, exploration and escape. Important as they are for the individuals these fleeting notions cannot provide the rationality for cities and societies to promote children’s cycling. Governments and policymakers are more concerned of the fact that children’s physically active and independent transport modes are important to achieve better public health, solve environmental challenges and increase related economic benefits.

Children cycling on the decline

Even though cycling is fun and enriching for the individuals and beneficial for the communities and societies around them, studies have pointed how all children’s independent mobility (CIM) has steadily declined in the industrialized world for decades. Adult chauffeuring by car has claimed precedence in children’s daily mobility patterns and public space. Some authors even argue that cycling children are something apart from the effective and purposeful use of public space in the city, and mobility spaces are not somewhere children belong. Excluding ‘childish’ use of mobility spaces constructs children as ‘incompetent adults’. In sum, it seems that children are encouraged to cycle (and their parents encouraged to let them cycle) for the sake of health, economic and environmental benefits by forcing upon them the instrumentally beneficial and functional rationalities of cycling-as-health-promotion and cycling-as-transport – even though cycling is likely to make sense for them for different reasons.

Studying framing of cycling promotion in Finland

How does this actually happen? Any cycling promotion initiative or policy process is laden with latent notions of the ‘cyclists’ that it aims to produce and ‘cycling’ that these people are supposed to perform. In other words, cycling promotion tends to privilege certain mobile subjectivities over others. In the paper we reflected on an action research study that was conducted in Finland in 2021 to find out how different taken-for-granted representations of ‘children’ as ‘cyclists’ emerged and interacted – and eventually created a rather impactful cycling promotion initiative thanks to devoted and open minded children and adults.

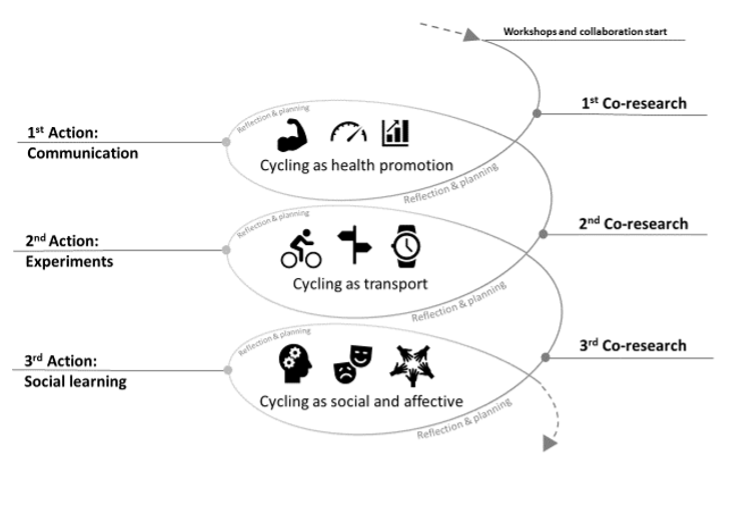

School trips are often considered the most important site of childhood cycling promotion, which neglects the multiplicity if important institutions that shape children’s lives and mobilities. Children’s organised after-school activities are a crucial part of contemporary childhood and parenting and to emphasise this, the project was carried out in a large children’s sports club, where the club personnel, local cycling advocates and families co-created a set of cycling promotion experiments (actions). We researchers mixed up the process by facilitating workshops and co-researching different issues and outcomes with the participants to instil critical reflections. Together these ingredients created a social learning process scrutinizing the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of childhood cycling promotion.

Cycles of action and reflections

In retrospect, the process entailed three partly overlapping cycles of reflection and action:

- First, cycling was perceived an act of health promotion with instrumentally beneficial collective and individual outcomes for children’s present and future well-being. The main action was communicating the benefits of childhood cycling to children’s parents. This rationality was understandable and acceptable for all adults in the project and helped to engage with the stakeholders. Yet, it represented children as passive recipients of new mobility practices and cycling as a disutility – useless time spent between destinations, which should be harnessed to provide quantifiable benefits.

- Second, the rationality geared towards facilitating children’s cycling as functional transport with a range of practical experiments where children were taught cycling skills and bicycle repairing. The experiments worked quite well, but children questioned the way that these practices were predefined in functional and adult-directed ways. This pointed to the problematic representation of children as ‘rational’ and functional users of mobility spaces and bicycles: cycling was reduced to moving from A to B. The representation of cycling as purely functional transport to which individuals engage based on rational decision has been widely criticised. Our study emphasises this problematic especially with regards to children.

- Third, the results pointed that the experiments had been successful, but mostly through mechanisms that were not recognized by the project organisers beforehand. Co-researching parents’ and children’s experiences made all participants assess the functioning of the project in a different way, where children’s sense of autonomy, positive emotions and friendships formed a rationality, that stood apart from instrumental and functional rationalities.

Balancing rationalities

We problematise some aspects of the instrumental and functional rationalities and representations of ‘children’ as ‘cyclists’ they entail, but the bottom line is that all three rationalities are necessary as cycling promotion policy processes and initiatives move from planning to implementation and finally into embodied and affective real life cycling practices. The study emphasises that balancing between the rationalities is not easy, even when supported by a conscious and evidence-based community learning process.

‘What makes children cycle?’ is an often heard but an unfair question with myriad possible answers. Our study highlights one part of the answer – the people, organisations and institutions around children. In conclusion we criticise the widely used term children’s independent mobility (CIM) as in stead of independence, interdependence on peers, adults and childhood institutions seems to be the key to success in childhood cycling promotion policies and initiatives. We argue that children’s autonomous mobility is a better term, that is more conscious of the fact that children don’t cycle (and parents don’t facilitate their children’s cycling) for the instrumental benefits or purely functional ends, but because it works for them socially and affectively.

If the adult society keeps building social and material structures as car-centric parenting norms, exclusive urban spaces and childhood institutions that are entangled with the car-system, we can hardly hold individuals responsible if rates of children’s autonomous mobility keep sinking. According to our findings, children do take up cycling and make it their own if the communities around them are committed to support it. Cycling promotion should not try to socialise children, the ‘incompetent adults’, into decent, rational and functional use of mobility spaces as this might only force an alienating rationality upon them.

Read full academic paper here (open access).

Citation: Silonsaari, J., Simula, M., Te Brömmelstroet, M., & Kokko, S. (2022). Unravelling the rationalities of childhood cycling promotion. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2022.100598.