“Urban mobility is not only the outcome of staging “from above” by planners, engineers, and designers, but also of staging “from below” by people themselves as they move throughout the city, performing and acting out their role as mobile actors”

(Jensen, 2013)

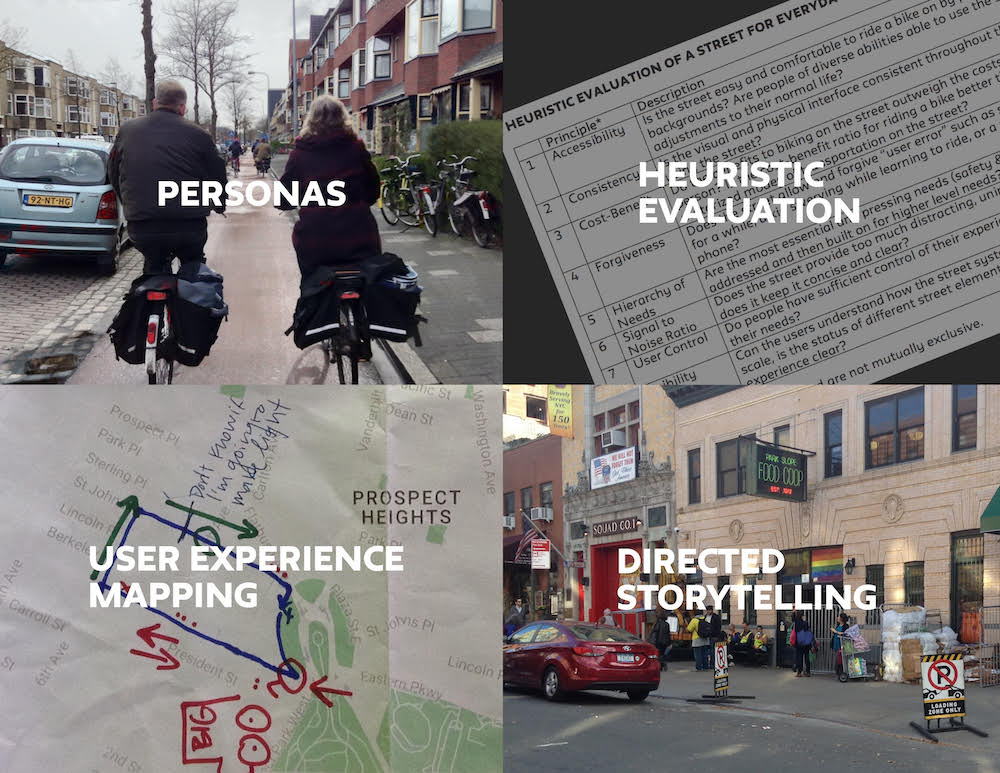

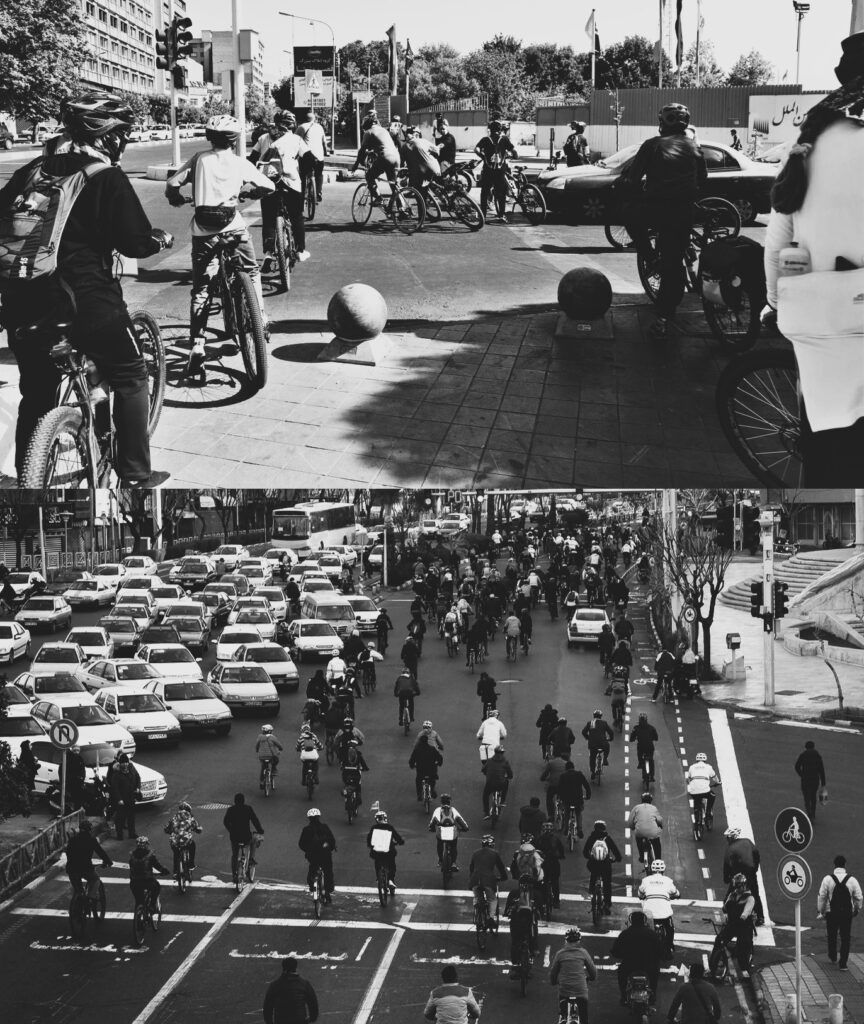

Every city is a special stage and has its own actors. Tehran and Amsterdam are very different in terms of active mobility! A bike-friendly city where cycling is the easiest way to get around; and a car-dominated environment where cyclists are a minority in places that belong to private vehicles. This essay focuses on a piece of my mobile lived experience in these two cities.

It is noticeable that the bicycle is emerging as a simple tool with tremendous benefits that can play an effective role in addressing complex urban challenges and transforming various aspects of our urban life. It can take over short trips, combine with public transportation for long trips, alleviate many environmental problems, promote individual and social community health, improve human relationships and social ties, build socio-cultural identities with others and places, and play a leading role in creating human-centered cities.

Despite these obvious benefits, cycling development in car-oriented environments is politically contentious and presents several contextual challenges. Tehran, as a car-dominated city suffering from severe environmental problems, has experienced ups and downs in urban cycling development over the past two decades and faces many challenges in staying on track with a long-term planning process due to a variety of factors that are beyond the scope of this essay. In spite of the bicycle’s prominence in Iranians’ collective memory, car culture has spread throughout most Iranian cities with the development of car-centric urban planning. As cycling activists, We work with different social groups and stakeholders involved in mobility planning to not Amsterdamify, but try to focus on culture and transfer knowledge and lessons to make our city more livable.

Bottom: Amsterdam

In contrast, Amsterdam offers a completely different perspective. Cycling is convenient, safe, and obvious in a city that has comprehensive cycling planning. However, Amsterdam wasn’t always as it is today. As the city became more car-centric during the 1950s & 1960s, it was a significant symbol of social movement. “It could have gone the same way as other European cities, which capitulated to the car, stimulated public transport, demarcated pedestrian areas, and eliminated bicycles from road traffic” (Feddes & de Lange, 2019: 34). The human-centric city we have today is the result of people, activists, and some policymakers rethinking the city and urban life. The story of Amsterdam is the story of urban transformation in which the bicycle is a leading actor! They transformed the city, the city transformed them.

For me as a cyclist in a car environment, the question is: Can it be achieved in other contexts as well? What lessons can be learned and transferred to other parts of the world, especially to places with low levels of cycling, such as Tehran? In car-centric environments, it is common to hear the statement “We aren’t Amsterdam” or “We cannot be like them!” which is a defeatist argument. By applying critical insights, Dutch cities can be viewed as learning platforms for transferable lessons and knowledge. Every city has its own opportunities to transform itself.

One of our city officials: But we are not Amsterdam!

Me: Yes! And Amsterdam wasn’t either. We can make the change we want!

Amsterdam is flat, it’s too hilly here to cycle!

Me: Have you ever tried a bike with gears or an e-bike?

People don’t use the cycle paths that already exist!

Me: Rethink infrastructure planning and think about human infrastructure!

Human infrastructure?!

Me: Yes! That means…

Oh! Sorry to interrupt! My car’s alarm system…!

Cycling in Tehran is a challenging experience. Powerful machines take over the streets and impose a heavy spatial hegemony on us. Car and motor drivers treat cyclists as annoying road users who don’t belong on the road, creating an anti-bicycle culture where cyclists feel neglected. They see themselves as insiders and consider us outsiders on the road. In such an unfair atmosphere, I look for a space to ride and ask myself: whose street? What role do I play on this stage?

This was a simple question when I was cycling in Amsterdam. The street is mine and as a cyclist, I am the leading actor on this stage. It was so easy and convenient to cycle in the stream of cyclists on the protected network. It is more convenient, faster, and more reliable to use the bicycle than other means of transport in Amsterdam. Separated, high-quality cycle lanes without conflicts with cars are something very different from my environment, where cyclists often experience stigma and harassment from other road users.

Bottom: Amsterdam

It is the perfect means to get around the city in Dutch contexts, with a wide range of symbolic values such as egalitarian culture, inclusive space, and freedom of movement for women, although in my context it is a crucial tool to challenge spatial hegemony, express citizenship and address gender equality. For Iranian women, cycling is a practice of representing power and challenging hegemonic sociopolitical structures from below and an emancipatory tool for transforming lived space to be publicly visible.

In a society where women’s rights are a pressing issue, cycling can be a way to challenge the dominant patriarchal discourse. The freedom of movement and independence that cycling brings can have multiple effects on the micro-dimensions of women’s daily lives, and bring about far-reaching changes in the gendered structures of society and environment. Iranian Women see cycling as a political practice to challenge everyday spatial regimes.

Right: Tehran

Despite its simplicity, cycling is a complex social phenomenon, and cycling is a meaningful practice that improves the social environment. Regardless of the context, a cyclist is open to others and creates social interaction in an uncomplicated way. Unlike cars, bicycles significantly stimulate interactions between cyclists. A bicycle is a triangulation tool (a popular term in placemaking) that increases the chances of social activities and relationships. It increases the possibility of (direct and indirect) interactions.

The driver is concerned only with steering himself to his destination, and in looking about sees only what he needs to see for that purpose; he thus perceives only his route, which has been materialized, mechanized and technicized, and he sees it from one angle only – that of its functionality: speed, readability, facility.

(Lefebvre, 1974: 313)

There is a high degree of openness between cyclists, and they easily engage in conversation with one another which leads to direct social interaction. We were introduced by bikes and easily became friends. On my bike, I have close social interactions with my cyclist friends (direct) and with other cyclists and pedestrians (indirect). It is not uncommon for me to meet cyclist friends while waiting for a red light to change or while riding on a bike path on some streets. As we ride our bikes, our social relationships become stronger.

Right: Tehran

Cycling is not only a physical movement from A to B, but also a critical bodily practice, a way of life, and a meaningful way to experience everyday urban life. Bicycle has the transformational power to make our cities more livable. There are also emerging grassroots movements and bottom-up initiatives that have developed around cycling and are providing new impetus and strengthening the human infrastructure of cycling in my context. In addition, with comprehensive and high-quality cycling infrastructure, significantly more and more diverse groups could be encouraged to cycle. We’re living in a global paradigm shift that is changing cities and a golden time for cycling; it doesn’t matter if it’s Tehran or Amsterdam. If we aren’t careful, the conquered dams will be lost.

Right: Tehran

References

- Feddes, F & de Lange, M. (2019). Bike City Amsterdam: How Amsterdam Became the Cycling Capital of the World. Bas Lubberhuizen.

- Jensen, O. (2013). Staging mobilities. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991 [1974]). The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith, Oxford: Blackwell.