Written by George Liu

While cycling is an incredibly efficient mode of transport, its limited speed and reliance on human power makes cycling an ideal vehicle for trips under 5 km (20 minutes at 15 km/h) but what about people who prefer to travel longer distances? After all, the average American commutes 25 km (one-way) to work, and before you conclude this must be because of sprawling land-use patterns, the average Dutch person commutes a similar distance. Regardless of whether we conceptualize this as people’s choice to live further away from work or as the necessary result of sprawling land-use, it seems there are benefits to being able to choose a job that is further from where you live, and being able to access jobs further away definitely gives more options for couples and families living together.

How can cycling and transit work together to provide an alternative to driving over longer distances? Local public transit, once factoring in wait time, is often slower than cycling. However, more comfortable and faster higher-order rapid transit is available within walking distance of only the densest (and expensive) neighborhoods. Is it possible to bring higher-order transit within the reach of more people with existing land-use patterns?

The solution may be thinking about cycling and transit as vehicles for providing a single, tightly integrated journey. The Dutch have been doing this in practice for a long time, but it wasn’t until the year 2000 or so, this cycling-transit combination started being conceptualized by academic literature. The recent popularity of bike sharing and electric micro mobility gives more flexibility than ever for car-free station access, and being able to successfully integrate two transport modes into single journey holds immense opportunity for the future of medium-distance commuting travel.

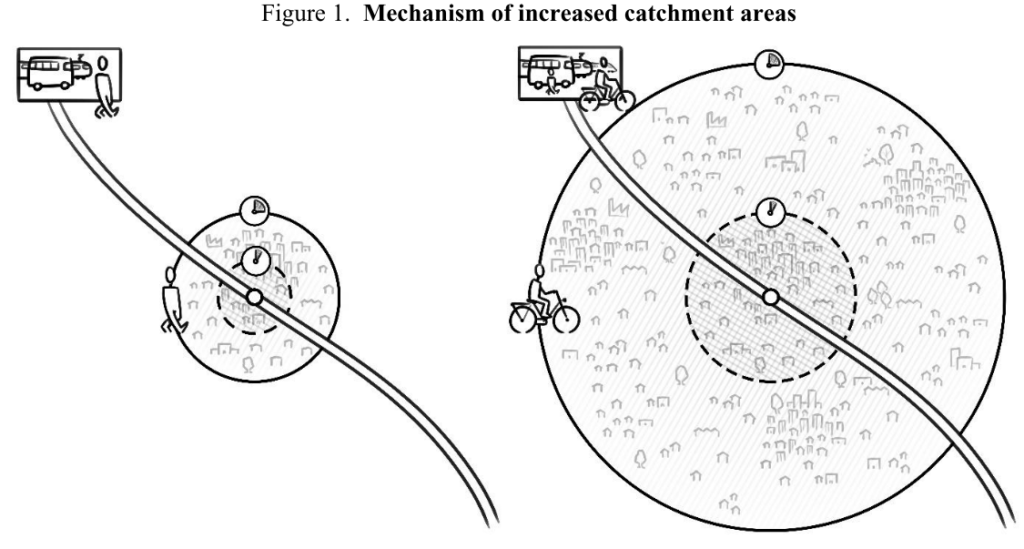

This paper investigates a transport system that is scalable to cater for urban mobility needs while sustainable and compatible with attractive streets and public space. It is the combination of two opposite yet synergistic transport modes: a) rapid mass transit for efficient, concentrated travel flows on the long hauls and b) walking and cycling for flexible movement of diffuse flows on short distances. Both modes are scalable, sustainable and don’t impair high quality public space. Yet, these modes on their own only serve highly distinct and partial travel segments. Integration of both modes should aim to tightly connect the strengths of each mode (speed and efficiency on long distance for transit vs. speed and flexibility on short distance for cycling) with the opposite weaknesses of the other mode (intrinsic low door-to-door accessibility of transit vs. limited action radius of cycling). An area with good cycling-transit integration then is one where cycling acts as a natural part of the transit system, offering a solution to the limited door-to-door connectivity problem of transit, or equally, where the transit system acts as a natural extension of the cycling system, offering a solution to the action radius problem of cycling.

Kager & Harms 2017 p.6

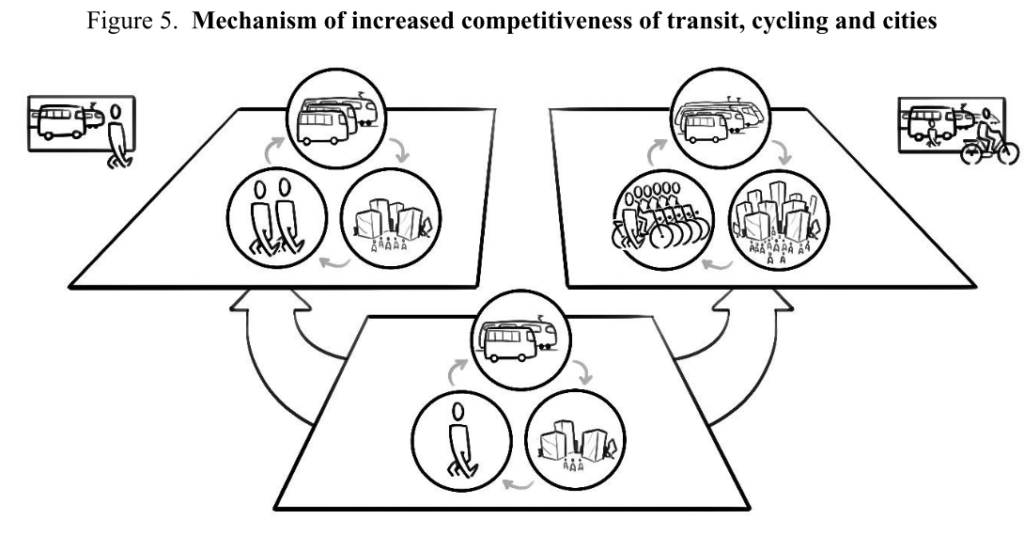

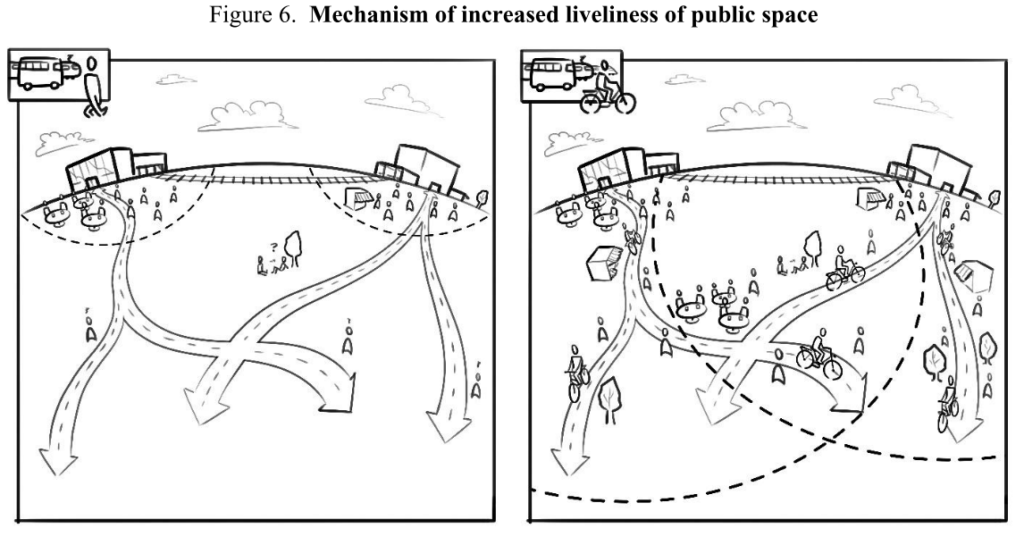

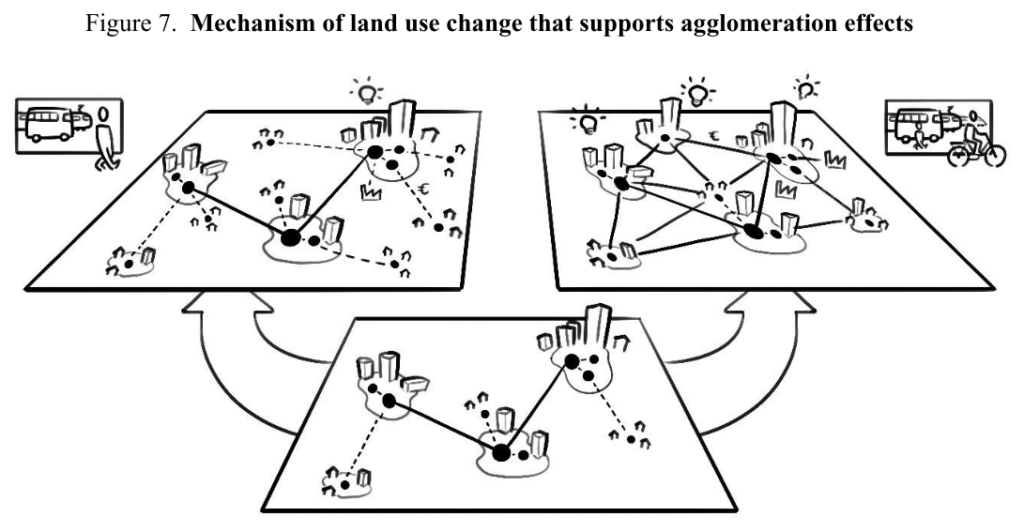

Let’s jump straight to Kager and Harms’ conceptual illustrations that really expanded my thinking about the potential of the system. I think these figures are the most impactful element of the paper, so let’s cover the seven mechanisms by which cycling-transit integration affects land-use and mode use. These seven mechanisms are:

- Increased catchment areas

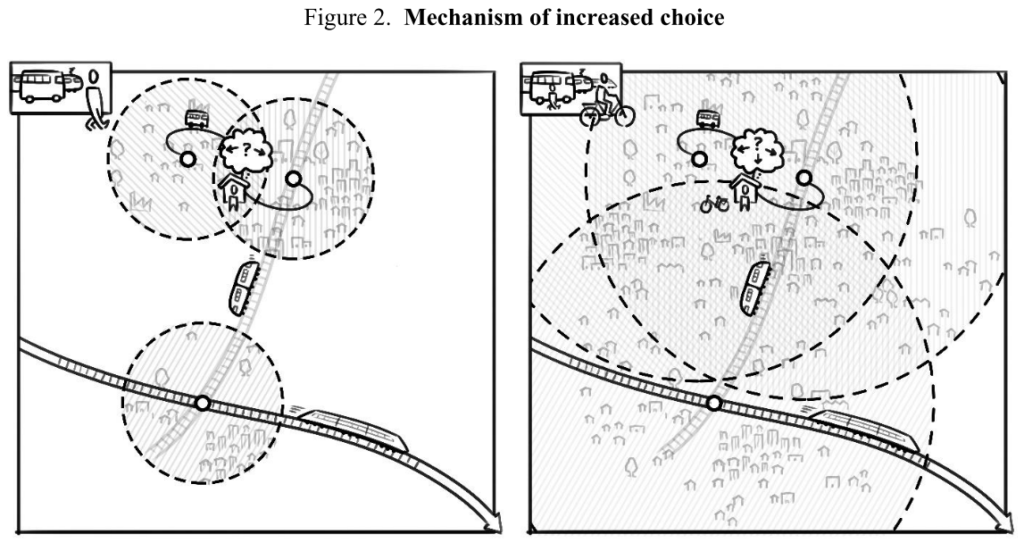

- Increased choice (including station choice)

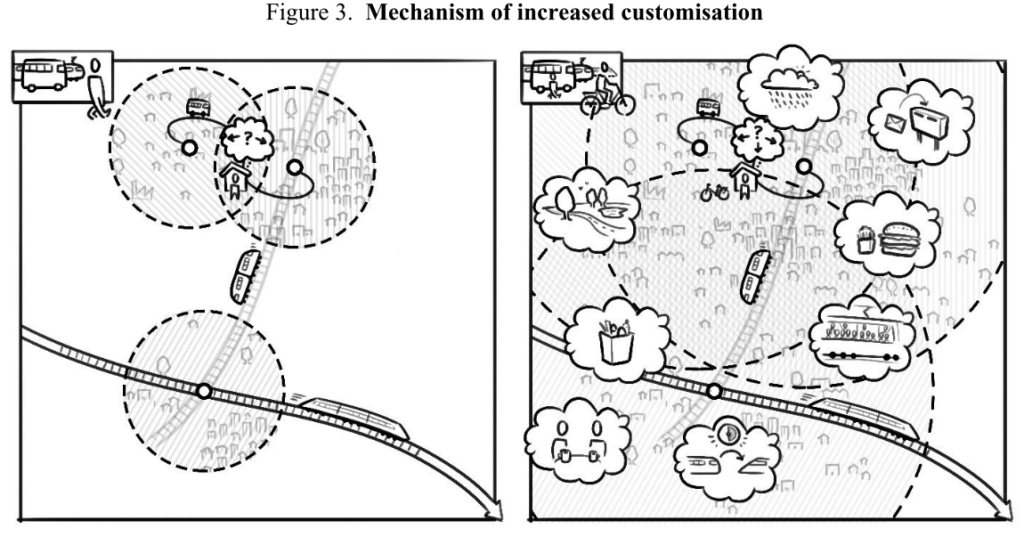

- Increased personalisation and customisation of transit journeys

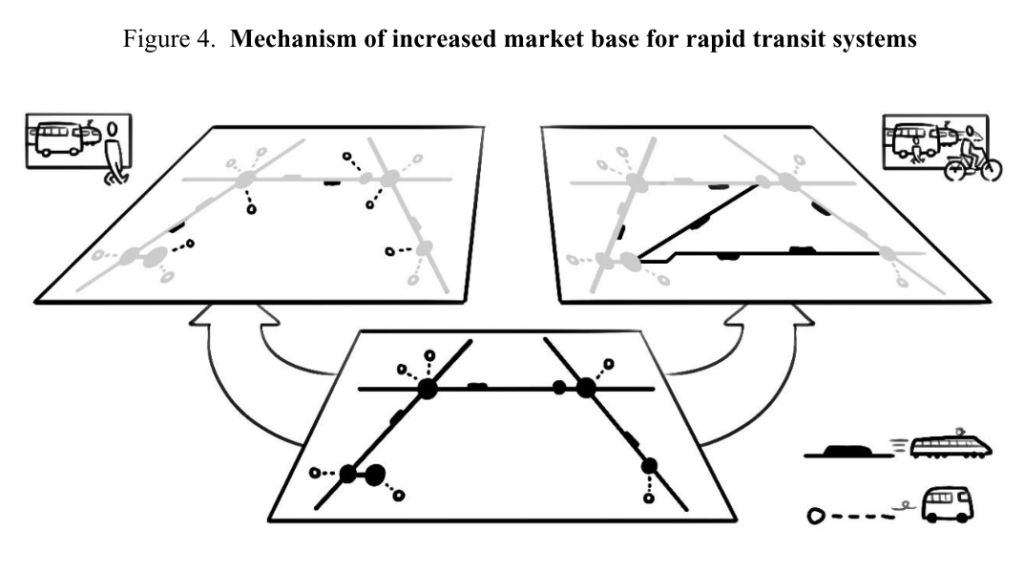

- Increased market base for rapid transit systems with more widely spaced stops

- Increased competitiveness of transit, cycling and cities

- Increased liveliness of public space

- Increased agglomeration effects

Dutch Case Study

In the Netherlands as a whole, most of my audience will know that 28% of all trips are made by bicycle, but it is less well known that 5% of all trips are made by train. It seems that the number of train trips is insignificant at first glance, but these number are equalized when we realize that the train dominates km traveled due to its faster speed: of all km traveled, 10% are by bike and 12% by train. Express bus services can serve similar travel demands as the train, but the train is used in the Dutch example because of its effective monopoly in longer-distance public transport.

The train accounts for just 5.7% of all daily transit services in the Netherlands and 21% of all service km, yet the train covers 97% of express services and 99% of express service km (>60 km/hr effective, straight-line speed). Also, out of all 365 transit stops in the Netherlands offering such express transit, 92% of these stops are railway stations… cycling and transit deliver disproportionally higher benefits when cycling is combined with rapid transit services. Nationally, bicycles are used for 47% of access travel and 13% of egress travel to train stations; usage is significantly lower in conjunction with local buses and trams.

Kager & Harms 2017 p.17

Cycling as an access mode brings express public transport (>60 km/hr) within a 20-minute (5 km) reach of 46% of the Dutch population, compared to just 10% who live within 1.25 km (20 min walk) of the same stations. Kager and Harms then go on to highlight the benefits of cycling-transit integration from both the traveler perspective and from the transit operator perspective.

From the traveler perspective, I think the mechanism of increased choice is the most overlooked element of current research. In many large cities, direct transit services are fragmented between many different stations, so being able to cycle to a station that is further away, but with a direct service may give a better journey experience than cycling to the closest station but incurring a transfer penalty

From the train operator perspective, cycling as an access mode provides a financial and service incentive to build faster regional transit with fewer and more consolidated stations.

Transit operators aim to serve ‘thick’ streams of demand: concentrated travel flows of passengers (the transaction base) over a sufficient distance (the fare base) while avoiding cost components such as halting times, indirect routes or speeds below economic base speed. From such a perspective, cycling offers a ‘helping hand’ to transform diffuse travel patterns into higher concentrations of travellers at particular stations, travelling in more concentrated flows to other connecting stations while requiring fewer intermediate stops.

Kager & Harms 2017 p.26

Most importantly, I think the greatest benefit from cycling-transit integration is its contribution to creating more lively and attractive public spaces by increasing the flows of pedestrians and cyclists in place of automobiles around the station area. Kager and Harms (2017) writes, “In contrast and unlike car-based accessibility, cycling-transit mobility steers away from distributive (sprawl) forces that work against the generation of agglomeration economies.” They conclude with a call to action:

The available list of flexible and scalable mobility strategies for urban agglomerations is not a long one, while the quest for a sustainable, effective and efficient urban mobility is pressing. The Dutch case (and initial developments elsewhere) shows us that improved cycling-transit integration can deliver effective and efficient urban mobility. The Dutch case (and initial developments elsewhere) shows us that improved cycling-transit integration can deliver effective and efficient urban mobility whilst not just compatible with urban agglomeration economies, but actually symbiotically feeding such economies.

Kager & Harms 2017 p.28

Citation of source article:

Kager, R., & Harms, L. (2017). Synergies from improved bicycle-transit integration Towards an integrated urban mobility system. International Transport Forum. Retrieved from https://www.itf-oecd.org/file/16904/download?token=z4vbf7mZ