Summarized by George Liu

Would urban design considerations and practices be different if the experience of bicycling was provided a more central place in key dialogues regarding the future of cities?” asks Forsyth and Krizek in the opening of this 2011 publication in the Journal of Urban Design. To answer this question, this paper juxtaposes the quantitative engineering approach of traffic experts with the more qualitative, user centered approach of urban designers. While the engineering approach seems to dominate bicycle planning today, this paper calls for a stronger role from urban designers in improving the experience of cycling by treating cyclists as more human than vehicle.

… cyclists have needs from the standpoint of urban design that substantially differ from pedestrians, motorists or transit users. Furthermore, it is contended that full provision for their needs is unlikely to come to fruition until their perspective is more formally acknowledged in research and through design guidelines. Therefore, this paper aims to respond to three questions. (1) What would it mean to create an urban design approach based on the bicycle in addition to, or instead of the motorized vehicle and the pedestrian? (2) What are the key dimensions of a View from the Road from the perspective of cyclists? (3) What are the implications for processes of city building, particularly sustainable design and urban redevelopment?

Forsyth and Krizek 2011 p. 532

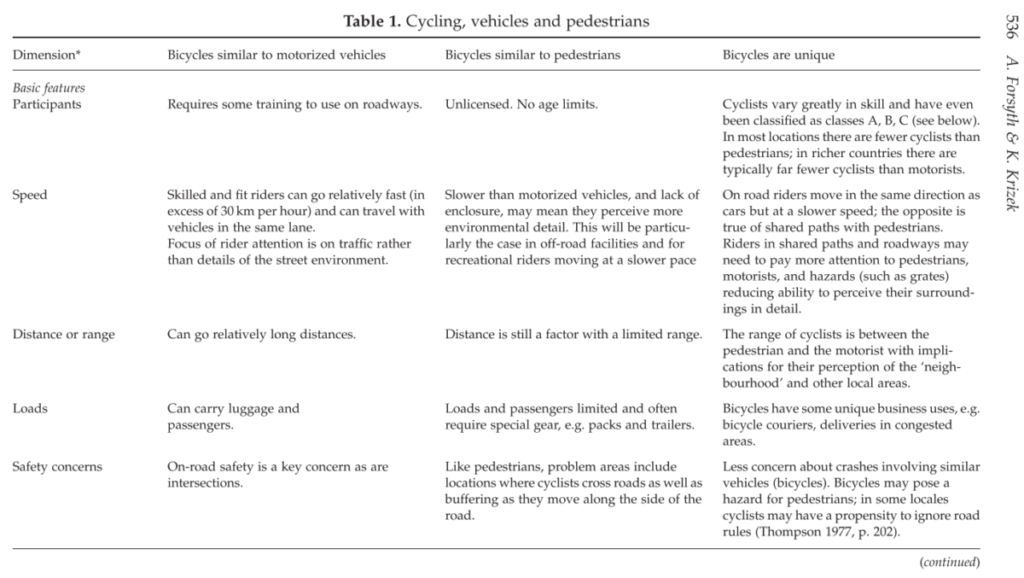

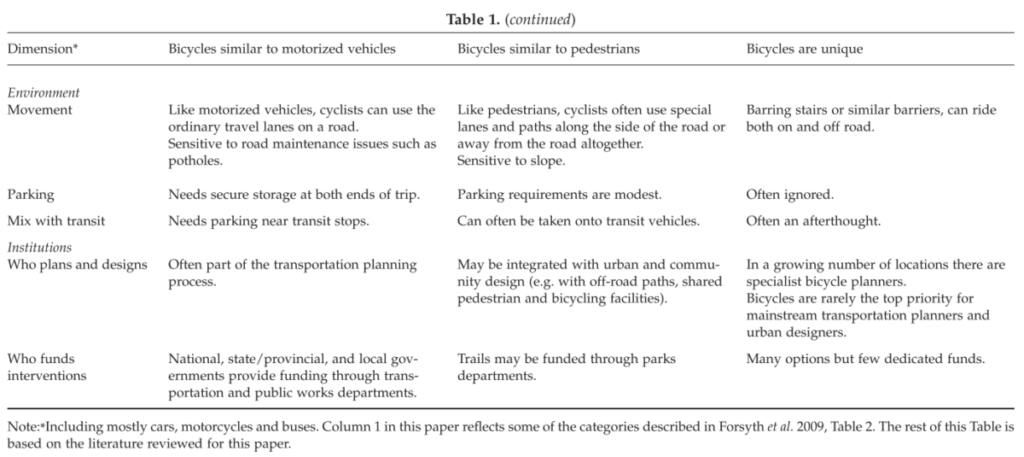

This paper seeks to understand the cyclists’ unique perspective by positioning cycling in the context of existing frameworks, both in relation to modality (automobiles vs. pedestrians) and in relation to urban design concepts (function, morphology, perception, social issues, aesthetics, and time). Conveniently, this paper summarizes frames of analysis in table format. I encourage you to visit these tables at their source, but as the PDF version of their paper has these figures rotated 90 degrees, I will directly reproduce them below in the upright orientation.

Similarity to Motor Vehicles vs. Pedestrians

Six Dimensions of Urban Design

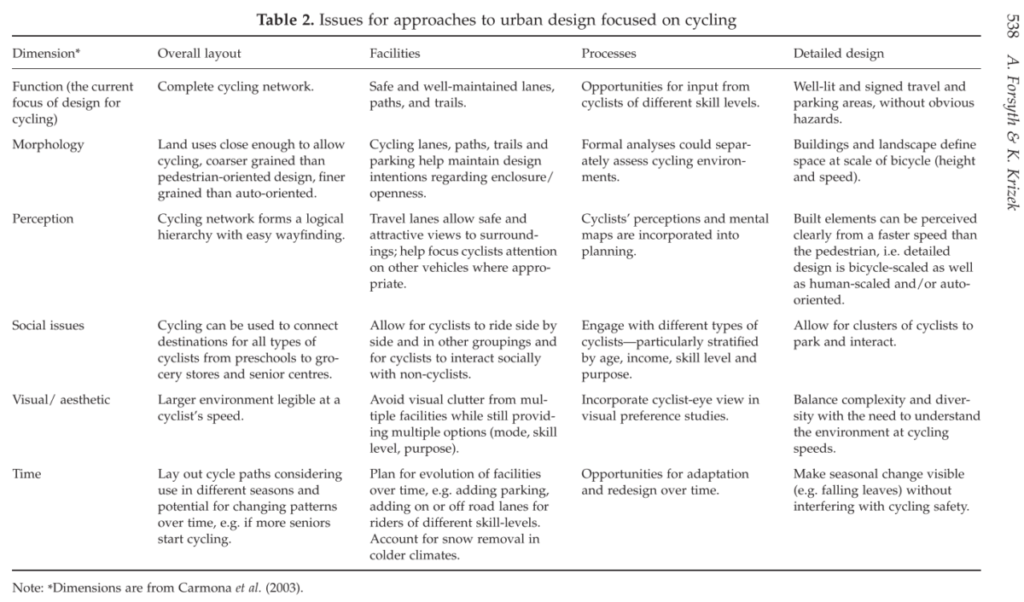

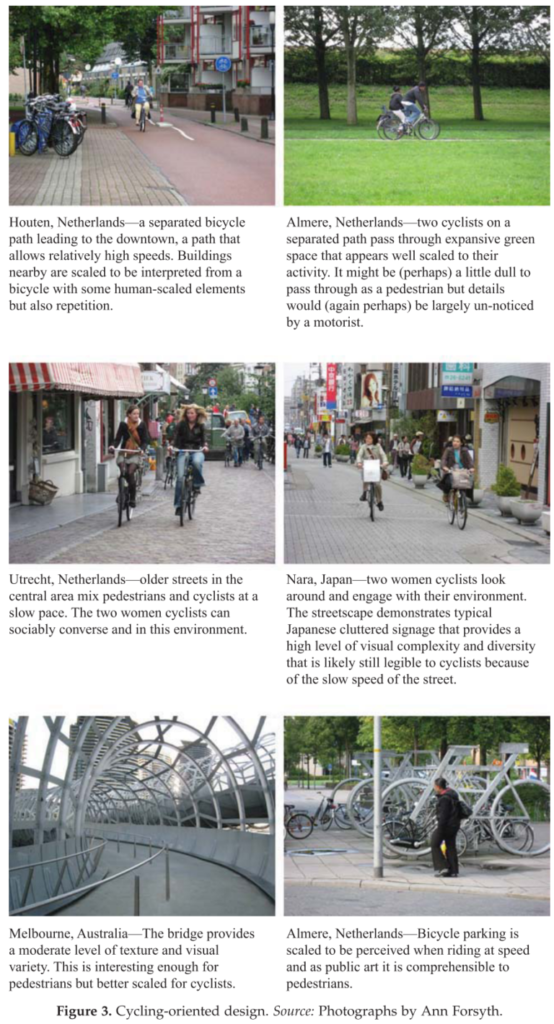

Of particular interest to practitioners is Forsyth and Krizek’s argument that, “Facilities for cycling have received far more attention than network layout from urban design and even transportation [planning].” If we are to consider the environment around the cyclist to play a role in cycling comfort, then it is easy to imagine that a cycle path through a forest or shared pedestrian space caters to a very different user than a bike lane along a highway. I argued in a previous post that, “often, the structural classification of a street may conflict with the design of the environment.

For example, a structural conflict may be the desire to move large amounts of automobile traffic through a pedestrian-oriented main street.” When considering cycling environments, it makes sense that even where functional infrastructure is the identical, such as a 4 meter bi-directional cycle path, the surrounding environment influences how users perceive attributes such as time, aesthetics, and social safety. The problem is, most design manuals and research focus on functional engineering standards, so bicycle planners receive little guidance on how to design for a better cycling user experience.

This paper then concludes with a few practical recommendations for transportation planners. Even on the issue of safety, which much research has been quite exhaustively conducted from a functional traffic perspective using serious injuries and deaths as indicators, cyclists’ perception of safety remains largely unexplored. They argue:

Safety—not so much in terms of crashes but violations from others—remains an untapped issue. Does providing more of a sense of enclosure for cyclists, or a cycle-eye street wall, have negative safety implications? It remains unclear if additional cycling infrastructure clutters the street environment, creates visual noise and under- mines the experience of other users.

Forsyth and Krizek 2011 p. 542

If I am to summarize Forsyth and Krizek’s call to action from both transportation planners and from urban designers, it would be their argument that, “Given that cycling lies squarely at the intersection of the domains of transportation planners and urban designers, planning and design processes have much room to acknowledge both areas of expertise.”

As with most academic papers, we leave with more questions than answers. What we do gain from this paper is a nuanced vocabulary to articulate why a purely functional approach to bicycle planning fails to provide a good cycling experience. In their call for future research, Forsyth and Krizek asks both transportation planners and urban designers to tackle the following critical questions:

- What types of forms are best perceived by cyclists given their height, position and speed?

- How can social interaction between cyclists and others be best considering both safety and the quality of experience?

- What level of visual complexity is most appealing for cyclists in different contexts?

- How can social interaction between cyclists and others be best considering both safety and the quality of experience?

- What level of visual complexity is most appealing for cyclists in different contexts?

- How can cycling environments evolve over time?

Citation of source article:

Ann Forsyth & Kevin Krizek (2011) Urban Design: Is there a Distinctive View from the Bicycle? Journal of Urban Design, 16:4, 531-549, DOI: 10.1080/13574809.2011.586239