The breakdown of the bicycle represents the socio-spatial separation between the “self” and the human/non-human “others”; fixing it yourself is a meaningful, self-determined practice to restore this relationship; and the Bike Kitchen can be an environment that collectively facilitates this.

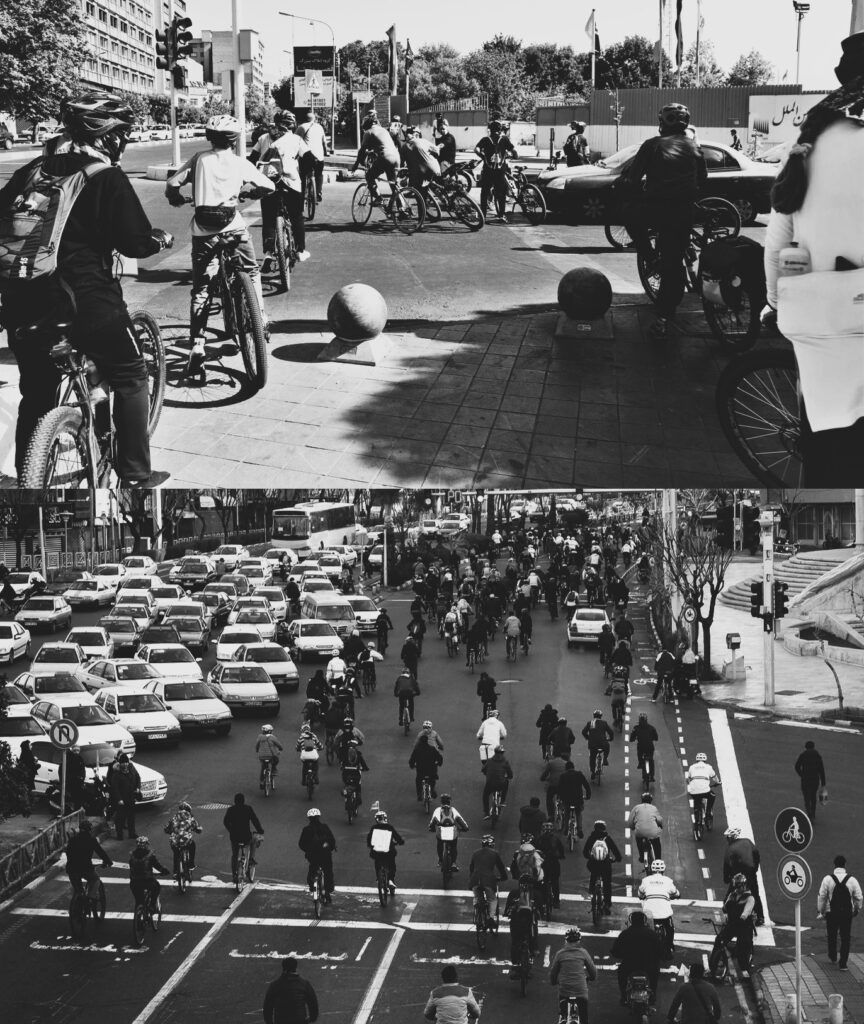

Right: The Bike Kitchen, Tehran.

What is a Bike Kitchen?

The Bike Kitchen is a DIY bicycle repair community workshop based on a non-profit basis where cyclists can fix their bikes, ask supervisors, and learn from others. Bike Kitchens started appearing in Europe in the 1980s (first in Vienna) and in America in the 2000s (Luna, 2012; Batterbury & Manga, 2022; Valentini & Butler: 2023). The basic idea is that people should have the necessary skills and knowledge to maintain and repair their bikes, rather than relying on expensive and often inaccessible professional services. By providing tools, spare parts, and expertise, the Bike Kitchen movement aims to empower individuals to take control of their own transportation needs. But Bike kitchens go beyond that in different contexts. I have engaged with two new examples of the Bike kitchen; one in a bicycle-friendly city (Amsterdam) and one in a car-oriented city (Tehran).

The literature overview shows that the Bike Kitchen is an open concept investigated through various theoretical lenses regarding different contexts. It can be a collective learning space for building a culture of sharing of space, tools and knowledge (Johnson, 2014); an example of the democratization of technology through non-capitalist relations in a degrowth context that protects the bicycle from being commodified (Bradley, 2018); a way to cultivate the conviviality of the bicycle as a convivial tool (Bradley, 2018; Batterbury & Baradar, 2023); a collaborative consumption and a commons-based peer economy against the dominated consumerist culture (Botsman and Rogers, 2011); and a social setting developing human-centered visions for re-imagining mobility and socio-material relations (Valentini & Butler: 2023).

Bike Kitchen UvA: Fostering student community and bicycle repair

The Bike Kitchen UvA is a learning and community hub for all things cycling which is located in the basement bicycle parking garage at the University of Amsterdam with the aim to empower students how to repair and maintain their bicycles. The Urban Cycling Institute and Kruitbosch are the co-founders of the Bike Kitchen. There is also an opportunity to become a member of the Bike Kitchen community. Romee Nicolai, Master’s student of Urban and Regional Planning at UvA, is the project manager and the work started in collaboration with ‘cycling professor’ Marco the Brömmelstoet, aims to increase the concept of circularity: ‘We make it tangible, by connecting knowledge and action and increasing ownership, pride and independence about a product such as the bicycle.’

It is a unique space that has transformed the traditional parking lot concept into a socially engaged and productive environment. While parking lots are typically considered functional spaces without social relationships or interactions, the Bike Kitchen has created a community-driven space where students can repair, customize, and maintain their bicycles while also engaging in social activities and learning about sustainable transportation.

The broken bicycles play a social role and provide an opportunity for triangulation (Whyte, 1980) between students. In this case, the bikes serve as both a physical and symbolic connection between students, fostering a sense of community and shared purpose. By providing a venue for students to work together on their bicycles, the Bike Kitchen fosters a sense of belonging and social connection that is essential.

I have experienced this space as a kind of third place (Oldenburg, 2001) that is socially produced (Lefebvre, 1974) and promotes face-to-face interaction, cooperation, and mutual support. Students learn how to connect their bikes with various repair tools to larger issues such as responsible consumption, environmental awareness, and promotion of conviviality.

Bike Kitchen Tehran: Strengthening the human infrastructure

Tehran is a car-dominated city, which has been built up through successive car-planning policies and long-term investment in car use over decades, along with a strong car culture that shaped people’s lifestyles, and reinforced car-centric urban planning. However, in recent years, the city has experienced ups and downs in urban cycling development. While cyclists are in the minority, cycling culture is emerging in Tehran. Activists and cycling groups play a significant role in strengthening the human infrastructure of cycling.

The first Bike Kitchens are springing up in Tehran. A space that enables collective learning and empowers cyclists. This is the space for activists to discuss and exchange ideas. Children and women who are marginalized in terms of mobility not only learn technical skills about bicycles in such Bike Kitchens but also expand their network of relationships.

Women cycling in Tehran is a challenge issue. In recent years, the groups and leaders of women cyclists have been able to significantly change the socio-political relationships surrounding cycling. Cycling gives them freedom of movement, makes them visible in public space, and challenges the existing gender order. From this perspective, Bike Kitchen is a space for the empowerment and networking of activists and marginalized groups that have a significant impact on raising awareness, strengthening the human infrastructure, and empowering communities through the bicycle.

Conclusion

Th Bike Kitchen is an open concept whose analysis from different angles, with different methods and in different contexts can produce different themes. An environment that at first glance is a simple place for repairing bicycles, but in its deeper layers it is full of meaningful relationships that connect it to larger social, political, cultural, and environmental structures that make it a complex phenomenon. Exploring different Bike Kitchens in different contexts can reveal further aspects of this complex socio-spatial fabric.

References

- Batterbury, S. & Baradar, H. (2023). Community bike workshops and bicycle repair: the global picture. Kooche, 4 (16), pp.76-83.

- Batterbury, S., & Vandermeersch, I. (2016). Community bicycle workshops and “invisible cyclists” in Brussels. In Bicycle justice and urban transformation (pp. 189–202). Routledge.

- Botsman, R., Rogers, R., 2011. What’s Mine Is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption Is Changing the Way We Live. Collins, London, UK.

- Bradley, K. (2018). Bike Kitchens – Spaces for convivial tools. Journal of Cleaner Production, 197, 1676–1683.

- Lefebvre, H. (1974) La production de l’espace. Paris: Ed. Anthropos.

- Oldenburg, R. (2001). Celebrating the third place : inspiring stories about the “great good places” at the heart of our communities. Marlowe & Co., New York.

- Valentini, D. M., & Butler, A. (2023). Bike Kitchens and the sociomateriality of practice change: exploring cycling-repair relations. Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 11(1).

- Whyte, W. H. (1980). The social life of small urban spaces. Washington DC: The Conservation Foundation.