Written by Jessica Rosenqvist | LinkedIn

Introduction

Has the European Commission considered the policies on gender that have been presented in the past and applied it to present day policies such as the Declaration on Cycling? It seems like there is awareness of gender differences in mobility, however, whether they will apply the actions that the policy note issued is unclear. This post will be discussing the CIVITAS Policy Note: Smart choices for cities – Gender equality and mobility: mind the gap! and the EU Declaration on Cycling and what they say about the issues in gender and mobility in Europe and how to get more people to cycle as well as some reflections of my own. CIVITAS is a program that helps the European Commission reach its mobility and transport goals and the Declaration on Cycling was drafted by the European Commission.

Efforts to gender mainstream in the mobility sector in the EU

There are considerable differences to women’s and men’s travel behaviour and the EU has focused on taking this into consideration. The policy note begins by mentioning how women’s travel patterns differ from men’s which are the following:

- Women travel shorter distances than men.

- Women are more likely to use public transportation.

- Women tend to trip-chain more.

- Women are generally safer drivers than men.

- Women tend to be accompanying other people such as children and the elderly.

- Women travel more outside rush-hour and engage in non-work related trips.

These are similar points that have been mentioned in academic literature such as Hanson (2010), Gauvin et. al. (2020), Aldred et. al. (2015), Heesch et. al. (2012) and Ravensbergen et. al. (2018). As Hanson (2010) and Ravensbergen et. al. (2018) have mentioned, there has not been a lot of discussion on gender in the mobility sector. The policy note is in agreement and explains that part of the issue is due to the lack of gender-differentiated statistics. I agree with this. However, as Hanson (2010) and Ravensbergen et. al. (2018) have said, looking at statistics is not enough as it does not help explain the social and geographical reasons for women to be behaving a certain way when it comes to mobility.

The EU is taking that into consideration and has had a gender mobility focus which was part of the ‘Strategy for equality between women and men 2010-2015’, where they have outlined actions that follow gender mainstreaming and specific measures. What they mean by gender mainstreaming is that the gender perspective is integrated into every stage of the policy process. I think that this is a very important approach as it allows women to have a voice from the design phase, all the way to the final evaluation phase. Gender-specific measures in transport planning means to have a more gender-sensitive approach in the urban and transport planning process by considering in what ways women travel the most and optimising and improving the infrastructure that they use or are exposed to.

Talks on sustainable transport but focus on cars remains

The Declaration on Cycling mentions gender and cycling but then concentrates on how to promote safe cycling and driving. The preamble to the Declaration on Cycling begins by stating that: ‘Transport is key for social inclusion and economic development, and for creating jobs and promoting access to other essential services, such as employment, education, health and care.’ However, transport needs to be done sustainably to achieve the EU’s climate objectives. That is where cycling comes in. However, different people have different needs when cycling and that is extremely important to take into consideration when creating bike lanes.

The declaration mentions that safety is an important aspect to get groups that cycle less, such as women, children and the elderly to get cycling, which shows that they are aware that women are more tentative when it comes to getting on a bicycle. However, they then shift their focus to cars and how they need to think about safety with cyclists. I agree that that is important to ensure safe cycling, however, there was no mention in that bullet point about the future decrease in cars and therefore a decrease in concerns for car and bicycle conflicts. If the goal of the EU is to decrease emissions, this also means to decrease the number of cars and therefore have a different outlook on how traffic should be regulated and structured.

Women’s mobility patterns are different to that of men

As has been seen above, women travel differently compared to men and therefore when considering inclusive mobility, these patterns need to be taken into consideration. The declaration mentions gender in their second chapter on inclusive, affordable and healthy mobility. They reiterate the need for cycling to help promote social inclusion and to pay attention in particular to what the women, children, the elderly and vulnerable and marginalised groups need. However they don’t elaborate on how they are going to do that, nor do they talk about what specific needs they have. They mention in the third chapter on better cycling infrastructure, the declaration mentions creating coherent cycling networks, protected bike lanes and safe parking spaces among others. However, they don’t mention anything about trip chaining or the differing travel patterns of men and women.

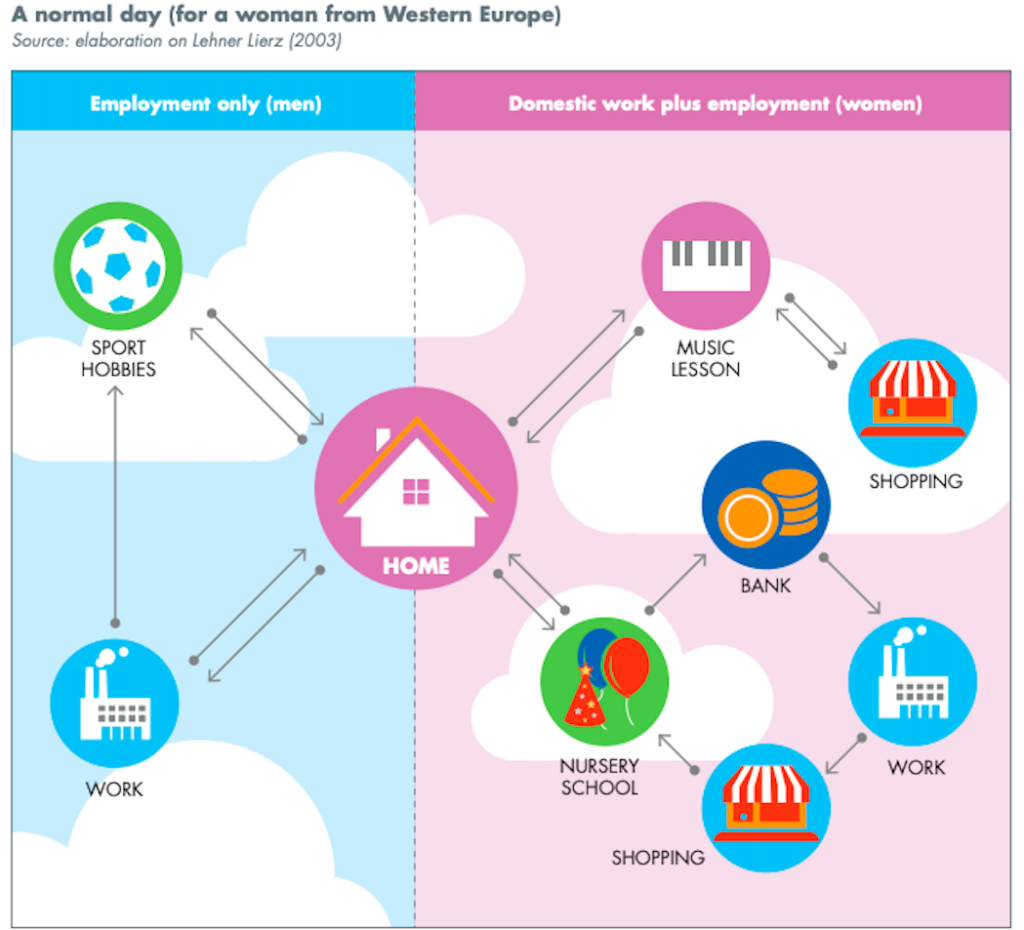

According to the policy note, When it comes to trip purposes, the data from various European countries show that women travel less for business and more for shopping, escorting family members and family management. This difference is more clearly seen in countries such as Spain and Italy where there are greater differences between men and women in the labour market. Another aspect to consider is trip chaining, when multiple stops are made before the end destination. As can be seen in the figure below, women and mens travel patterns are very different, with the normal day for men involving commuting to work and then to a hobby, whilst for women it is more complex, involving more stops between work and home, travel from home to other destinations other than work, not travelling alone, travelling outside rush hour and travelling shorter distances.

This does remind me of my childhood growing up, where it was the mothers who picked up the children from school and took them to extracurricular activities as well as did the shopping during the weekdays, not the fathers. I also saw this trend in Amsterdam when I was visiting, where children were almost exclusively accompanied by women. Due to these travel patterns, time lost in travelling affects women more than men and if new bike paths do not consider women’s travel patterns, they will be less likely to cycle.

Source: elaboration on Lehner Lierz (2003)

Conclusion

I am aware that the Declaration on Cycling is a very concise document, meant as an overview of what the European Commission wants to achieve in promoting cycling. However, I feel that there should have been a reference to gender mainstreaming or gender specific measures to demonstrate that they have understood that getting women to cycle is not just as simple as creating protected bike lanes and safer traffic conditions. The policy note, as well as academic papers such as the ones by Aldred et. al. (2016) and Heesch et. al. (2012) mention differences in travel behaviour between men and women, which shows that they are aware of the types of differences gender has on mobility. Other papers such as by Hanson (2010) and Ravensbergen et.al. (2018) go deeper and look into the context and feminist theories of why women cycle less or travel less than men.

The declaration did not go into any detail when they mentioned gender and women in cycling, which poses the question whether they fully understand how they will ensure that they will create bike infrastructure that will accommodate both men and women equally. I guess it will be a matter of waiting and seeing what bike infrastructure will be created.

References

Aldred, R., Woodcock, J., & Goodman, A. (2016) Does More Cycling Mean More Diversity in Cycling?, Transport Reviews, 36:1, 28-44, DOI: 10.1080/01441647.2015.1014451

CIVITAS Policy Note: Gender equality and mobility: mind the gap! (2014)

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – Proposing a European Declaration on Cycling (2023)

Gauvin, L., Tizzoni, M., Piaggesi, S. et al. Gender gaps in urban mobility. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7, 11 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0500-x

Hanson, S. (2010). Gender and mobility: New approaches for informing sustainability. Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, 17(1), 5–23.

Heesch, K. C., Sahlqvist, S., & Garrard, J. (2012). Gender differences in recreational and transport cycling: a cross-sectional mixed-methods comparison of cycling patterns, motivators, and constraints. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(1), 1-12.Ravensbergen, L., Buliung, R., & Laliberté, N. (2019). Toward feminist geographies of cycling. Geography compass, 13(7), e12461.

You can also take a look at other essays by Jessica Rosenqvist on mobility and cycling on the website:

Gender and Mobility: How Does Gender Affect Women’s Movement?

Gaining a deeper understanding of cycling and gender through feminist theories