What is the lived experience of cycling in urban settings? How important is it to understand the experience of cycling? How does the anthropological perspective and use of ethnographic methods contribute to cycling research? What can ‘autoethnography’ reveal about the lived experiences of the cycling researcher?

This essay looks at cycling from an anthropological perspective and discusses methodological issues for research on cycling experience using autoethnography. This interpretive ethnographic method has strong connections to phenomenology and the Mobilities Paradigm and presents an insider’s viewpoint of cycling practices. The purpose is to response to the request for studies on cycling from the anthropology perspective (Verstappen, 2023) and encourage the use of autoethnography to unfold the phenomenological aspects of cycling routines in different urban environments.

Cycling from an Anthropological Perspective

According to “Mobilities Turn” or “New Mobilities Paradigm” (Sheller & Urry, 2006), cities and places, in addition to their fixed and static aspects, are also defined by their movement. A mobilities approach means that we cannot understand people, things, and ideas only as rooted in specific places; we must also pay attention to the moving experiences, flows, and networks that connect humans to each other and to non-humans (Jaffe & Koning, 2016).

This new paradigm caused sociology and humanities to pay attention to mobile practice, including cycling. However, discussions about cycling have not yet had as much impact on the discipline of anthropology (Verstappen, 2023). The few anthropological studies are very prominent ones in cycling research (for example: Vivanco, 2013; Lugo, 2018). Cycling from this anthropological turn is not only a physical movement from A to B, but also is a cultural, social, and political practice influenced by embodied and lived experiences which can be interpreted through ethnographic methods within everyday life.

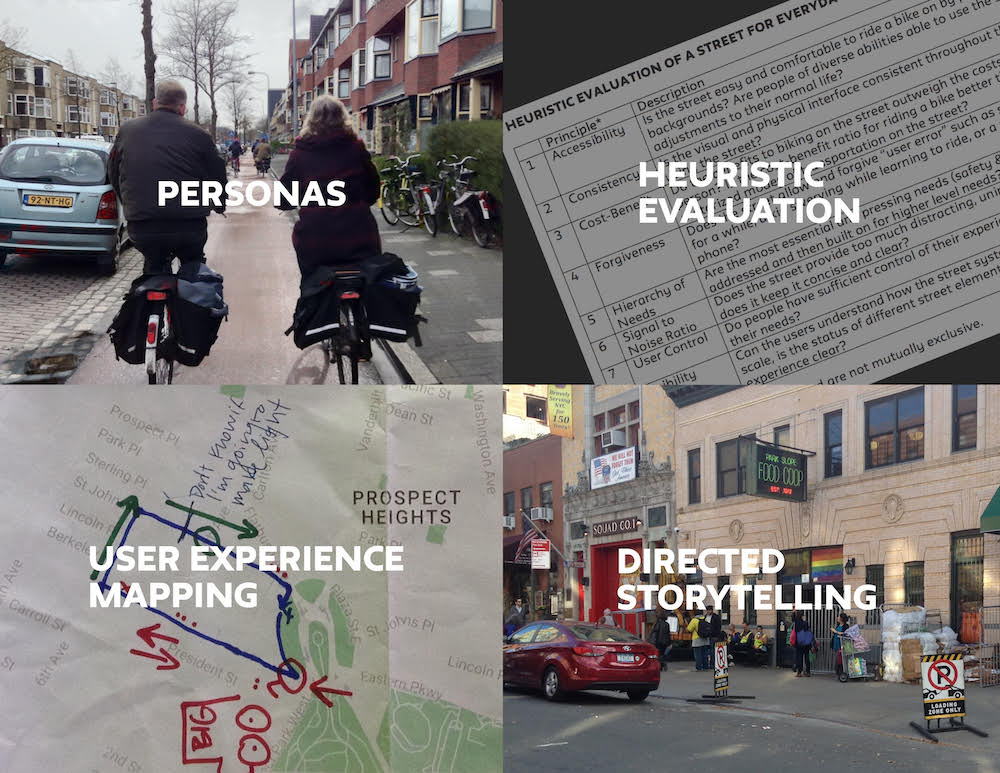

Therefore, we need innovative ethnographic methodological toolkits for understanding mobile experiences; toolboxes that can capture the meaningful aspects hidden in the deep layers of the lived experience of cycling actors to develop interpretive context-based theories of cycling practices. For instance, ethnographic methods can help researchers understand how cyclists perceive and navigate their surroundings, how they interact with other road users, and how they experience the city from a cyclist’s perspective.

Ethnographic and Autoethnographic Methodology

In recent years, innovative methods for understanding moving experiences have emerged, while the researcher engages in the studied moving practices and collects data by immersing in the embodied, fluid, and multi-sensory experience of movement through multisite ethnography. It means that the researcher should be able to engage in “empathetic learning” (Cox, 2019) through “learning with” (Ingold, 2000) mobile actors, and as a new form of “Active Participant” (Laurier, 2010) based on collective mobile experiences with participants, explore and understand different layers of lived experience. “Whilst the orthodox instruments of transport geographers, such as stated preference surveys and traffic counts might tell us something about the ‘rational(ised)’ push and pull and factors for cyclists, they fail to unlock the more ‘unspeakable’ and ‘non-rational(ised)’ meanings of cycling, which in no small part reside in the sensory, embodied and social nature of performance” (Spinney, 2011) .

Mobile methods allow us to be on the move with informants and make sense of their mobility patterns and grasp their subjective moving experiences. In cycling research, the most fundamental question is how cycling can change urban experiences and mobile methods can provide insight into the embodied, sensory aspects of cycling practice in different contexts.

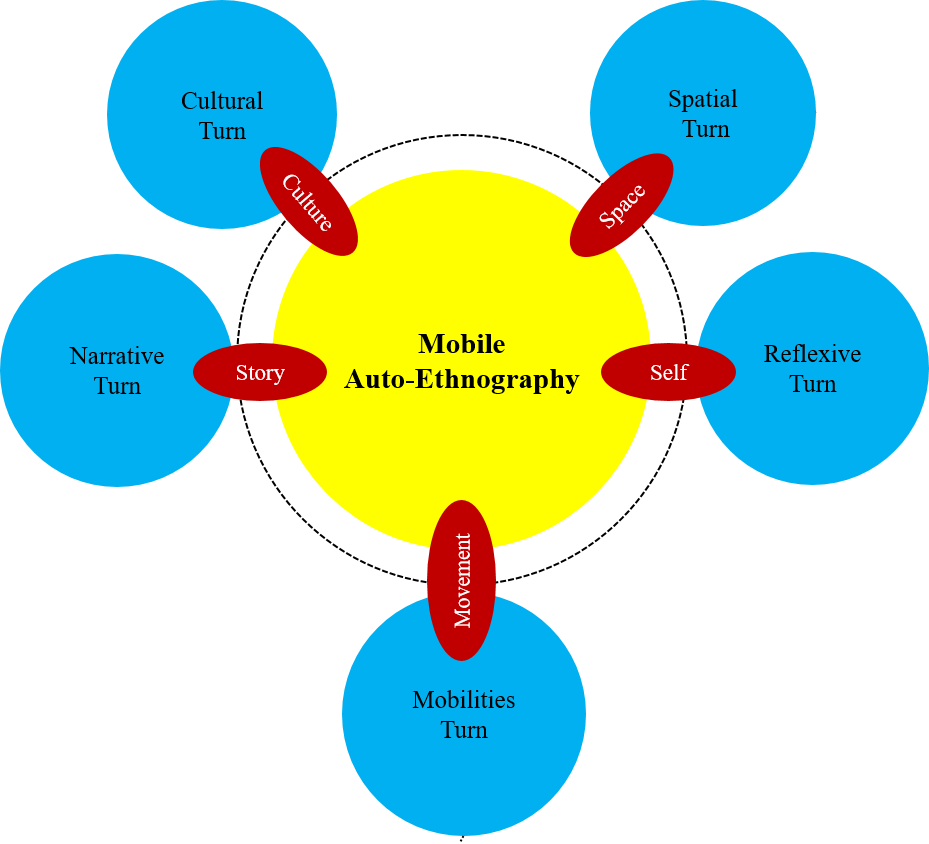

Among emerging mobile methods, auto ethnography seems to have more potential for understanding moving experiences. Auto-ethnography is a qualitative interpretive ethnographic approach to research that seeks to describe personal experience to understand cultural experience. Auto-ethnography is a research method that uses personal experience (“auto”) to describe and interpret (“graphy”) cultural texts, experiences, beliefs, and practices (“ethno”) (Chang, 2016). Personal stories are the main core and storytelling is the best way to understand the subjective experiences of the researcher that provide a useful way of knowing about the collective cultural experiences (diagram 1).

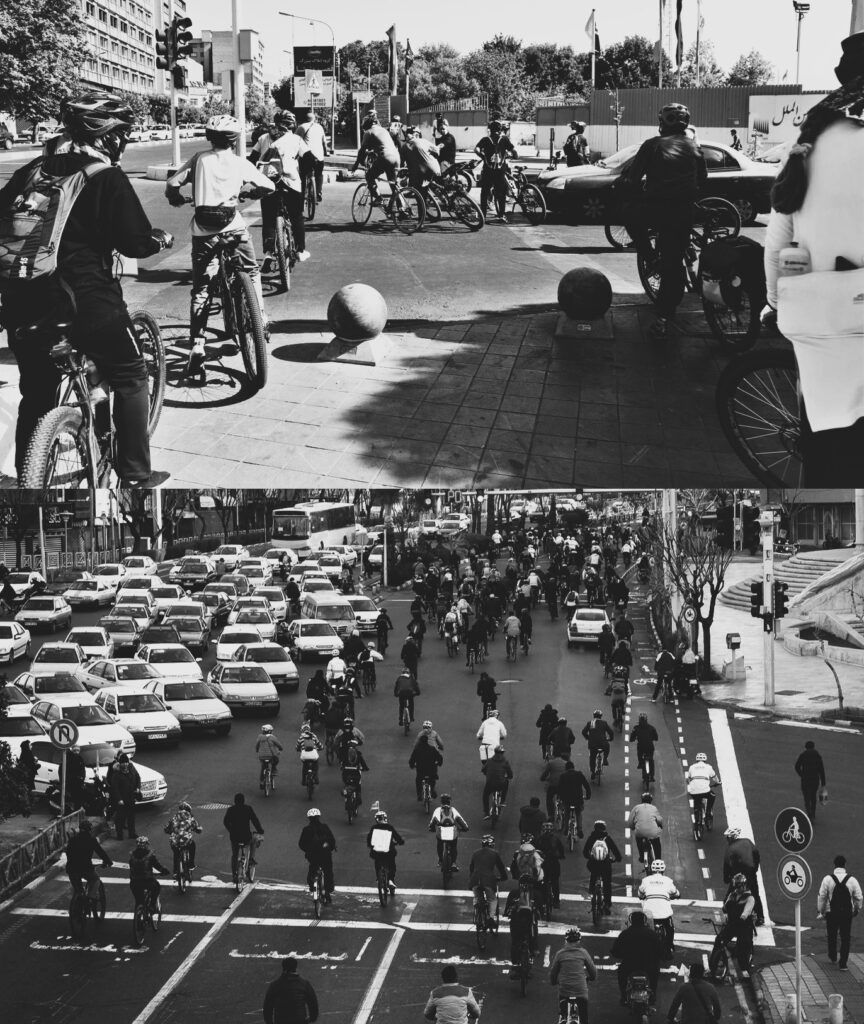

Mobile Autoethnography as reflexive method can provide an insider perspective (emic view) on cycling lived experiences within urban fabrics. I consider it among some interdisciplinary turns (diagram 2) that seek to understand the mobile lived experience of movement practices (mobilities turn) in the cultural context of everyday life (cultural turn) by describing the researcher’s narratives (narrative turn) regarding the subjectivity of the researcher (reflexive turn) and focusing on the idea that space is socially produced (spatial turn).

Cycling Lived Experience: Body/Space/Time/Human Relationships

Mobile Autoethnography is efficient for understanding lived experience of cycling. It is closely tied to phenomenology and the mobilities paradigm. Cycling auto-ethnographers write about their personal experiences that explore the depth layers of the subjective and inter-subjectivity lived experience related to the specific cycling culture from an emic perspective. It uses multiple data sources to collect field data and, therefore, can conduct in-depth ride-along interviews, and use photos, videos, documents, etc., as data triangulation in cycling research. There are a few examples in cycling research (Larsen, 2014) and it also can be conducted in collaborative participation (Nazarpoor & Saedi, 2020; Ravensbergen et al., 2023).

The four existential lifeworlds (Van Manen, 1997) can be used in autoethnographic cycling research: Lived space (spatiality), lived body (corporeality), lived time (temporality), and lived human relations (relationally) (table 1). Interpreting these lifeworlds can provide a deeper understanding of the lived experience of cycling in various urban settings. These dimensions can be used as a research agenda for future studies with the aim of understanding the lived experience of cycling from the perspective of urban anthropology.

| Lived space | The way we perceive space is challenging issue within everyday mobile lived experiences. Riding a bike is a form of spatial resistance which requires the demand of space within unequal distribution of space. In most cities, public spaces present themselves as a disputed space for urban cyclists. |

| Lived body | Cycling is tied up with bodily resources. The body is the main tool through which cyclists move, explore and experience their surrounding environment. During the ride, my body is the pivot of the world and develops my lived spatial knowledge. |

| Lived time | Cycling has its unique cyclical rhythm, depending on our gender, physical abilities, and type of the bicycle, which is engaged with the pulse and rhythm of the city and creates a unique experience in and of urban spaces. |

| Lived human relation | Being and dealing with others is the foundation of everyday life. Cycling has a plurality of meanings and is influenced by a myriad of social dynamics. It is a social process that extends social relations across aspects of the urban spaces within a specific context that improves social environments. |

Conclusion

Travelling by car, using public transport, walking and cycling seem to offer radically different levels of interaction potential, especially with people outside one’s own social network and with the physical environment (Te Brömmelstroet et al., 2017). The lived experience of cycling is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that involves both physical and emotional aspects.

The anthropological point of view and the application of ethnographic methodology can provide valuable insights into the cultural, social, political, and emotional dimensions of cycling in various urban contexts. Autoethnography can provide a thick description of the researcher’s lived experience and link it with different dimensions of cycling practice.

Read one of our autoethnographic essays on cycling experiences in Amsterdam and Tehran: Being on the stage: Cycling as a political act or as a part of lifestyle? and another of external Autor: Ethnography on the Move: Doing Fieldwork on a Bicycle

References

- Brömmelstroet, M. T., Nikolaeva, А., Glaser, M., Nicolaisen, M. S., & Chan, C. W. (2017). Travelling together alone and alone together: mobility and potential exposure to diversity. Applied Mobilities, 2(1), 1–15.

- Chang, H. (2016). Autoethnography as method. In Routledge eBooks.

- Cox, P. (2019). Cycling: A Sociology of Vélomobility. The Mobilization Series on Social Movements, Protest, and Culture. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. (2002). The perception of the environment. In Routledge eBooks.

- Jaffe, R., & De Koning, A. (2015). Introducing urban anthropology. In Routledge eBooks.

- Spinney, J. (2011). A chance to catch a breath: Using mobile video ethnography in cycling research. Mobilities 6 (2) , pp. 161-182.

- Larsen, J. (2014). (Auto) Ethnography and cycling. International journal of social research methodology, 17(1): 59-71.

- Laurier, É. (2010). Being There/Seeing There: Recording and analysing life in the car. In Palgrave Macmillan UK eBooks (pp. 103–117).

- Nazarpoor M, Saedi M. (2020). Understanding Lived Experience of urban Cycling in Tehran (A Collaborative Auto-ethnography). Urban Design Discourse; a Review of Contemporary Literature and Theories; 1 (2).

- Ravensbergen, L., Ilunga-Kapinga, J., Ismail, S. R., Patel, A., Khachatryan, A., & Wong, K. (2023). Cycling as social practice: a collective autoethnography on power and vélomobility in the city. Mobilities, 1–15.

- Sheller, M., & Urry, J. (2006). The New Mobilities Paradigm. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 38(2), 207–226.

- Sheller, M., & Urry, J. (2006b). The new mobilities paradigm. Environment and Planning A, 38(2), 207–226.

- Van Manen, M. (1997). Researching Lived Experience, second edition. (2016). In Routledge eBooks.

- Verstappen, S. (2023). Worlding cycling: an anthropological agenda for urban cycling research. Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 11(1).

- Vivanco, L. (2013). Reconsidering the bicycle. In Routledge eBooks.