Interview with Léa Ravensbergen | LinkedIn

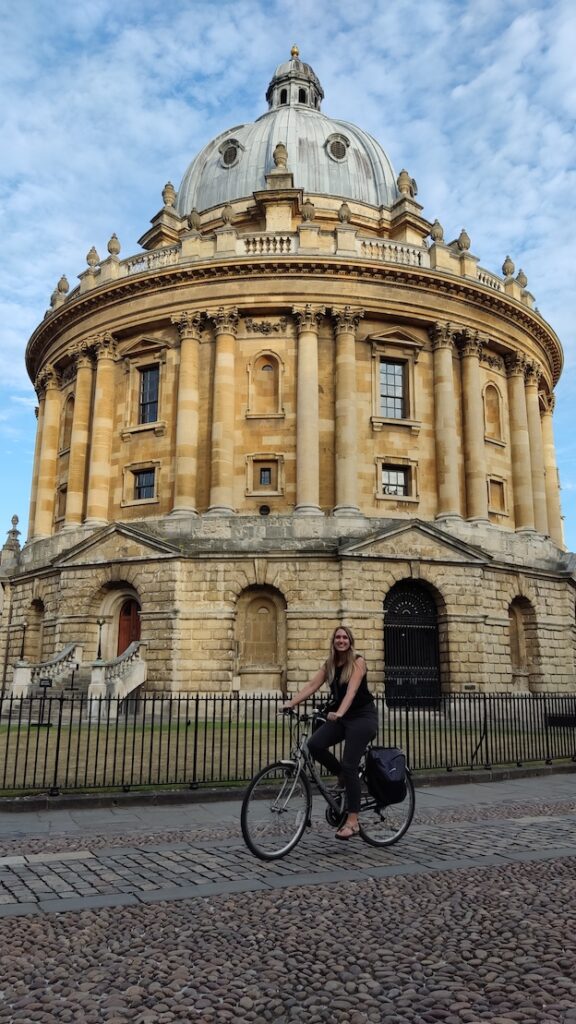

Conducted by Jessica Rosenqvist | LinkedIn

I am Jessica Rosenqvist and had the opportunity to interview Léa Ravensbergen, one of the authors of Towards Feminist Geographies of Cycling, an assistant professor in the School of Earth, Environment & Society from McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. We spoke about her motivation to write the paper, her thoughts on gender and cycling and her ideas on the topic in urban policy. A summary of her paper is available here: Gaining a deeper understanding of cycling and gender through feminist theories.

What is the backstory of writing your paper?

I was a keen cyclist, I feel like I understood the city through the bicycle and the bike was my primary mode of transportation when I lived in Montreal and when I moved around and when I was a master’s graduate student. And I was always interested in cycling and got excited about cycling research.

But when I was reading the research, especially the research on the gender gap in cycling, on how women cycle less than men, it just really felt like it was written by men and for men. To the point sometimes where it was a little bit insulting, some of the ways that the findings were being interpreted, and that this focus was very much on women’s problems and why women aren’t able to cycle as much, as if there’s something about being a woman that makes it hard to cycle. And I found that quite upsetting and was like, surely we can think a little more deeply about this than just women are scared or, women take care of kids so there’s nothing we can do, they just can’t bike. It felt kind of like the conclusion that was being drawn from this research, which I found quite upsetting and not very representative.

And I was always interested in feminism. So that was what motivated it was a want to have more nuanced and better conversations about gender and cycling and wanting to have different voices represented in gender and cycling. And then eventually wanting to take down patriarchy in general because I realised the relationships there between that and mobility.

How do you see your work taking shape in urban policy?

The first step is just the overarching goal to dismantle the patriarchy or the white supremacy or classism or like all of the other power structures. That’s your first goal. But part of that is building lots and lots of nice, safe bike lanes and quiet streets and things that keep in mind children and older people and women, people with different levels of skill, different expertise, people who are a little wobbly on their bikes, people who are extremely fast. Think about all those different people when you’re building it to make a nice, safe cycling city.

And thinking about care is my third one. So if you’re able to do that trip chaining and to get the groceries on your way to work or to drop off your kids on your way to work with your bike, that’s brilliant, and I want more of that. We really have a bias in North American cities of planning cycling infrastructure to get to work. We plan all of our transit to get to work. And I get it, but we’ll even have the case where, I go close to the grocery store, but to actually get to the groceries, I need to cross a horrible parking lot full of trucks and SUVs. And I feel like those destinations are just completely not thought of, or rarely thought about, amongst bike planners.

So, think about care. Think about everyone and keep doing your hard work and remember that part of what you’re doing and part of that overarching goal is dismantling patriarchy and other unfair power structures. And they’re all related. So by making it easier to get to the grocery store by bike, you’re doing your part, but that they’re all related. And at the end of the day, I’d love to live in a city where people can do care by bike comfortably and safely, but that it’s not mostly women that do it, that it’s shared more equitably, like it’s the kinds of things that we just keep in mind throughout.

It also helps you realise that a cycling policy is also a daycare policy. You might be a transport planner, but if you’re a transport planner and there’s, like we have in Canada, a big debate about having a subsidised federal daycare policy, that policy is related to your work, like it or not, whether or not women can access affordable daycare is going to affect how they travel, which is going to affect your work so they’re related. So you can’t just think of them as different. So you need to think more holistically of all of that. That would be my two cents for all of that but I know that can be intimidating. But the number one goal at the end of day is to dismantle the patriarchy. In the meantime, there are lots of things we can do to play our little role because it is all related.

How do you see your work in the global context where cultural customs are vastly different?

Yeah, that’s a good question. Most of my work is in Canada, that’s where I’m from and where I live. So, it is kind of based on that, but I do think that there’s a problematic tendency to think that cultures and customs are all that different in other places, and that patriarchy is here too. A lot of that is actually shared. I had that a lot when people would talk a lot about in some cultures, you know, that access to skill is really gendered and women aren’t encouraged to bike, and isn’t that very really sexist, we don’t have that in Canada. And you go, well, if you actually look at the statistics, about the age of 12 or 13, girls stop playing sports, and girls do have less access to the bicycle than boys do here too. Like, a lot of these things are shared. You just don’t notice it because it’s your life, so it’s become normalised.

So I prefer looking at the similarities and the differences, but I also think that my work and a lot of the work is very biassed because a lot of it comes from the global north or a lot of it’s from North America or from Europe. And I really would like to see more coming from other contexts. And maybe it’s out there and it’s just not published in English, and that’s why I haven’t seen it yet. Or I know there’s other barriers to, you know, the academic process. So if you want to talk about biases when you want to say patriarchy, try publishing when English isn’t your first language and you’ll see the biases. You can have excellent research and still not get accepted. So maybe it’s happening and I’m just not aware of it, but I also think there’s a great opportunity for people in other contexts to do a lot of this great work. I’m sure they can add a lot to the conversation and I could learn a lot from them.

You’ve already published a lot of papers since you’ve published Towards Feminist Geographies of Cycling. But what’s next for your research?

Well, I’m doing a lot on care, mobility of care, and how people travel to meet their care needs, which is what got me started when I was doing that (Toward Feminist Geographies of Cycling) work. I’m really interested in how or how we don’t currently think about getting people children to where they need to go or older dependents to where they need to go or health needs or grocery needs. And I’m doing a lot of work on ageing as well, and how we plan around ageing mobility. And part of that is gendered as well, like who does the mobility for older people when they can’t do it for themselves. So that’s the area that I’m moving toward, but still that interest in equity and sustainability and what we are not looking at is still front and centre in what I hope to be doing in the next few years.

You can also take a look at another essay by Jessica Rosenqvist on mobility and cycling on the website:

Gender and Mobility: How Does Gender Affect Women’s Movement?